Haarlemmer Houttuinen Housing

Main objectives of the project

The primary objectives of the Haarlemmer Houttuinen Housing project in Amsterdam were to establish a lively and community-focused environment. Architect Hertzberger aimed to create an intimate, pedestrian-friendly street, limiting access to residents' vehicles. The design prioritized fine-tuned scale, fostering a sense of community, and incorporating distinctive architectural elements to enhance the unique character of the residential quarter.

Date

- 1987: Construction

Stakeholders

- Architect: Herman Hertzberger

Location

City: Amsterdam

Country/Region: Amsterdam, Netherlands

Description

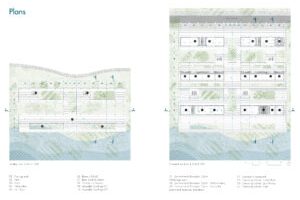

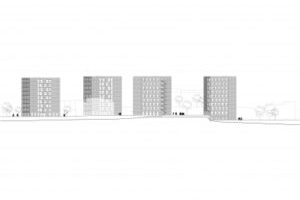

The Haarlemmer Houttuinen Housing in Amsterdam is squeezed between a busy main road and railway to the north and Haarlemmerstraat to the south. The north block was built by Hertzberger, the one to the south by the architects Van Herk & Nagelkerke. The two blocks are separated by a pedestrian street connected to Haarlemmerstraat by two gateway buildings also designed by Van Herk.

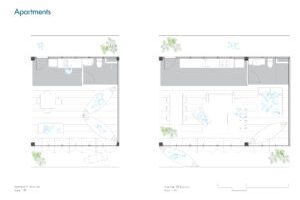

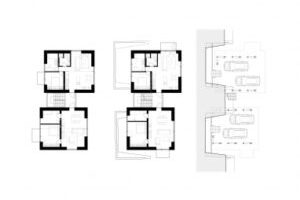

Hertzberger s housing block has projecting piers with balconies that give rhythm to the street. Each pier marks the entrance to four maisonettes and supports the balcony of the upper two. All entrances to the dwellings are off the street and balconies and gardens overlook it. Fine-tuning of scale is

achieved by tiles in the centre of the lintels and the granite pads supporting them, and by the different sized square windows which syncopate rhythms and let in light along the ceilings where window heads have been kept closed to give intimacy within.

Hertzberger wanted the new street to be a lively community area. The street is accessible only to residents cars and delivery vehicles. With the street closed to general motorised traffic and measuring only 7 metres in width, an unusually narrow profile by modern standards, a situation is created reminiscent of the old city. Street furnishings such as lights, bicycle racks, low fencing and public benches are distributed in such a way that the passage of traffic is obstructed with only a few parked cars. Some trees are planted to form a centre halfway between the two street sections. The lower maisonettes can be entered from their tiny gardens in the street, while the upper units can be reached by external stairs to a shared landing at first floor level, where the front doors are. While the extended block on the north side of the street provides shelter from the busy main road and railway behind it, the south-side block is one storey lower to allow the sun to shine in the street. In this respect, the scheme reinstates the original function of the street as a place where local residents can meet. Streets which no longer serve exclusively as traffic thoroughfares are increasingly seen on the new housing estates and in urban renewal projects. The interests of pedestrians are being taken into consideration, and with the recognition of the woonerf as a street space in a residential area where pedestrians enjoy legal protection against traffic, they are slowly regaining their rightful ground. The decision to reserve a strip 27 metres wide fl anking the railway for traffic purposes forced Hertzberger to build up to this imposed limit of alignment. As a result there was no room on this side for back gardens, which might in fact have been permanently in the shade. Unfavourable factors such as undesirable orientation and traffic noise meant that the north side would have to accommodate the rear wall, and so automatically all emphasis came to lie on the street side which faces south. The north side has no entrances or balconies. The long, continuous rear wall forms a sort of city wall marking the limits of the residential quarter and setting it apart from the railway viaduct, the open area beyond and the harbour in the

distance. In order to involve the rear view in the architecture, the upperstorey dwellings were given bay windows. These are the only plastic features in an otherwise unarticulated wall.