Pere Garau social housing, Mallorca

Main objectives of the project

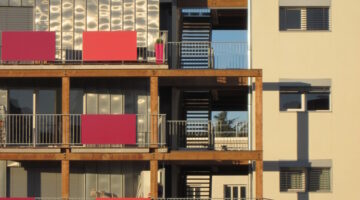

The project in the Pere Garau neighborhood of Palma transforms a corner plot, once characterized by single-family dwellings, into a new public housing building amidst urban gentrification. It adheres to regulations while creatively utilizing the space, fostering a dialogue with neighboring structures. The resulting design features a perforated solid, housing individual narratives within a shared framework. Terraces integrate indoor-outdoor living, while shutters maintain privacy and solar control. This approach not only addresses housing needs but also preserves community identity in the face of neighborhood change.

Date

- 2012: Construction

- 2008: Ganador

Stakeholders

- Architect: RipollTezon

Location

City: Palma de Mallorca

Country/Region: Palma de Mallorca, Spain

Description

The project is located in the ‘Pere Garau’ neighbourhood of Palma (Mallorca). The area used to be characterised by blocks of single-family dwellings with interior courtyards following a typical grid plan. Once the district became a central area of the city, modifications in urban planning significantly increased building volumes and changed the typology to collective housing. The project is part of this transformation by redefining a corner plot, resulting from the union of two old houses, into a new public housing building. Moreover, it does so in a context of change in the neighbourhood. Pere Garau used to be one of the most vulnerable neighbourhoods in the city of Palma. Now it is undergoing a clear process of gentrification, the result of which could lead to the expulsion of residents. The commitment to social housing can prevent this.

The building is conceived respecting the volumetry prescribed by the regulations and taking advantage of the established rules: a buildable depth and the possibility of overhangs towards the street, half of which can be occupied with closed surface. The proposal takes advantage of this situation to create mechanisms that relate the dwelling to its immediate surroundings through openings in the volume.

The result is a perforated solid where the realities of each of the inhabitants resemble scenarios stacked one on top of the other. It is a universe of small stories organised according to a non-apparent order, whose layout arises from the relationship that the building establishes with the adjoining buildings, seeking in this dialogue to be sensitive to their scales, heights and morphology.

The different rooms of the dwelling will be organised around fixed bands that house the server packages. The excavated terraces will link interior and exterior, allowing the direct radiation of the sun and the light that penetrates to be controlled, as well as offering a landscape of its own, incorporated in the foreground of each dwelling. The rest of the openings will be protected with shutters facing the façade.

The building won the public competition to build with IBAVI, the public promoter in Mallorca. It offers 18 housing units for families. Moreover, it has won the “Ciutat de Palma 'Guillem Sagrera' de Arquitectura” 2013 award and ended up finalist in the 5th Architecture Award of Mallorca.