Bhuj, a historic city in Gujarat, India's westernmost state, has served as the administrative center of Kutch District since 1947. Situated in a region prone to extreme heat, droughts, earthquakes, and cyclones, Bhuj faced a significant setback when it was nearly flattened by an earthquake in January 2001, causing the loss of 7,000 lives and leaving thousands homeless. Within Bhuj, there exist 76 slum settlements, accommodating approximately one-third of the city's population, yet residents lack secure land tenure. These slums, organized along religious and caste lines, often originated from land allocated to lower-caste communities in exchange for services rendered to the city by historical authorities. Despite their ancestral land rights, most residents are still regarded as squatters on public land since Indian independence in 1947.

In 2010, a pivotal change began with Sakhi Sangini, a federation of women's self-help groups, conducting Bhuj's first comprehensive survey of slums. Recognizing challenges in drinking water supply and housing, Sakhi Sangini, along with Kutch Mahila Vikas Sangathan (KMVS) and Hunnarshala, initiated projects to address these issues with modest donor funding. This initiative evolved into the Homes in the City program, aiming to improve housing, sanitation, water supply, waste management, and livelihoods. Although successful in empowering 120 vulnerable families to upgrade or rebuild their homes using low-interest loans and technical support, the program faced limitations due to insufficient funds. The introduction of the Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY) Program provided a promising solution. Unlike typical government slum redevelopment schemes led by contractors and developers, RAY aimed for a different approach, acknowledging Bhuj's unique circumstances.

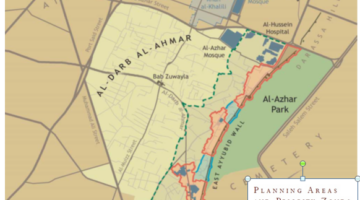

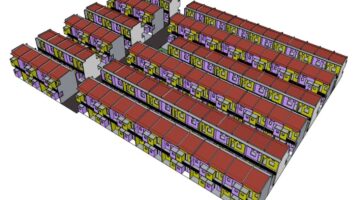

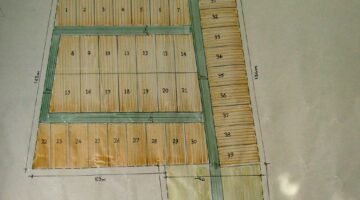

Recognizing the importance of outdoor spaces and community cohesion, a study conducted by students from the Center for Environmental Planning and Technology (CEPT) in Ahmedabad highlighted that most families in Bhuj's slums occupied 60-80 square meters of land. This finding emphasized the need for a participatory, community-driven housing reconstruction pilot. As a result, a comprehensive plan was devised, involving 314 households across three slum areas. Each household was allocated 65-square meter plots with full infrastructure and permanent land tenure, ensuring community involvement and satisfaction. This broke with how the public sector usually works. Rather than making high-rise buildings made by private promoters, the subsidies were given directly to residents, building community housing.

The initial focus was on Bhimrao Nagar, housing 42 families from the Marwada community, bestowed the land by the king of Bhuj. Out of these, 37 families opted to reconstruct their homes on the same site. Remarkably, five houses in Bhimrao Nagar, constructed with durable materials and in good condition, were exempt from rebuilding. Instead, they were integrated into the project, receiving equivalent tenure rights and infrastructure subsidies as the others.

Following Bhimrao Nagar, attention turned to Ramdev Nagar, an ancient settlement occupied by impoverished families for decades, spanning multiple generations. The dilapidated houses, constructed from tarpaulins, plastic sheets, mud, and cement blocks, highlighted the urgent need for redevelopment. All 116 houses in Ramdev Nagar were slated for reconstruction. Notably, five structurally sound houses in Ramdev Nagar were spared from demolition, included in the project, and granted the same benefits.

Lastly, the GIDC Resettlement site emerged as a temporary refuge following the 2001 earthquake's devastation. Among the 300 shelters in GIDC, 156 were earmarked for rebuilding in the initial phase of the RAY program.

Bhuj distinguished itself by embracing the RAY program through a community-driven approach, a rarity in Indian municipalities. The 314 slum families participating in the pilot project received subsidies directly from the local government, enabling them to collectively construct their homes. Facilitated by members of the Sakhi Sangini women's savings federation and supported by the NGO Kutch Mahila Vikas Sangatan, extensive consultations were conducted across the implementing communities to ensure clarity on the terms, subsidies, and operations of the RAY program. Ultimately, unanimous agreement was reached among the families in the three pilot communities to partake in the scheme.

Prior to the project's commencement, residents in all three communities lacked legal tenure status, relegating them to the status of squatters on public land. Technically, the land they occupied, spanning several generations in some cases, fell under the jurisdiction of the Central Government's Revenue Department. With the approval of the RAY project, the land was formally transferred to the Bhuj municipal government under a 99-year lease. Upon completion of the project, the 314 families involved will receive individual allotment certificates for their 65 square meter land plots, effectively granting them ownership of their dwellings. However, as per the RAY program's stipulations, families are prohibited from selling or transferring their land or houses for a period of 15 years following occupancy.

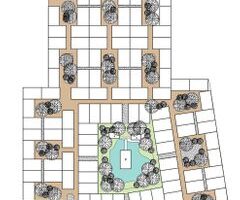

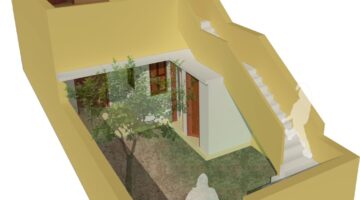

In each of the three settlements, the inception of the project marked the formation of slum committees. This step was pivotal as it signified the communities' transition from informality to formal inclusion within the legal framework. Those assuming roles in these committees underwent regular training and sensitization sessions facilitated by the women's savings federation and KMVS. These sessions covered a range of topics, including social, physical, and financial aspects crucial for collectively managing both the housing project and the resulting residences. The comprehensive redevelopment of all three communities entailed the creation of new layouts, houses, and infrastructure. The design process was collaborative and participatory, involving a series of workshops where architects engaged with community members, particularly women, to explore the strengths and weaknesses of their previous settlements and devise plans for their replacements. The layout designs underwent continuous refinement and adjustment, with finalization occurring only upon unanimous approval from all families across the three settlements.

The final layout plans for all three communities in Bhuj were carefully crafted to align with typical settlement patterns found in both rural and urban areas. Emphasizing communal living, houses were organized in clusters around common open spaces, fostering social interactions and providing safe areas for children to play. Beyond housing and basic amenities, the redevelopment plans aimed to enhance overall quality of life by incorporating social and community facilities such as community centers, shops, day-care centers, and health clinics.

Environmental sustainability was a key consideration, with efforts made to retain existing trees and introduce more greenery to increase shade coverage. Basic infrastructure services like metered municipal electricity and water connections were provided to each house, supplemented by innovative "green" solutions such as rainwater harvesting systems and localized water treatment. Additionally, street lights powered by solar panels ensured well-lit common areas at night.

Unlike traditional government-led redevelopment programs, the 314 Houses project in Bhuj stands out for its community-driven approach. By directly empowering residents with subsidies from the RAY Program, they were able to construct their own homes, showcasing the expertise of skilled artisans within the slum communities. This participatory model not only resulted in faster and cost-effective construction but also demonstrated the ability of communities to design and build housing more effectively than conventional government interventions.