Plan B, Guatemala

Main objectives of the project

In response to the devastating Volcán de Fuego eruption, Plan B Guatemala, led by the ASIAPRODE Association and designed by DEOC Arquitectos, offers a sustainable and adaptable housing model for affected families. The 86m² homes, constructed with durable materials such as concrete blocks and bamboo, feature a unique design that separates living spaces into two blocks with an interior courtyard, promoting natural ventilation and community interaction. This design supports the rural lifestyle and allows for future expansion. The self-build concept enables families to tailor their homes, reducing waste and fostering a sense of pride and community cohesion.

Date

- 2019: Construction

Stakeholders

- Architect: DEOC Arquitectos

Location

Country/Region: Guatemala

Description

On Sunday, June 3, 2018, the Volcán de Fuego, situated between the departments of Sacatepéquez, Escuintla, and Chimaltenango in Guatemala, erupted twice. This disaster resulted in numerous fatalities, thousands of evacuations, many people in shelters, hundreds of injuries, and nearly two million individuals affected. Plan B Guatemala was established in response to the catastrophic eruption of Volcán de Fuego. The ASIAPRODE Association initiated this project to construct 26 homes to meet the needs of the affected communities. In an open competition, DEOC Arquitectos presented a proposal that adhered to the established requirements, the user profile, and the natural context.

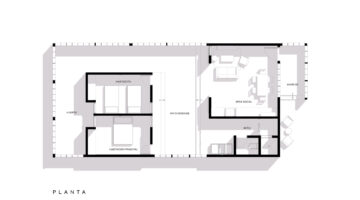

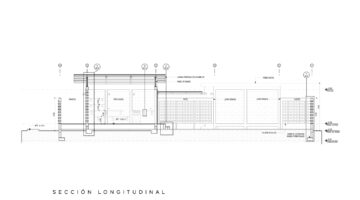

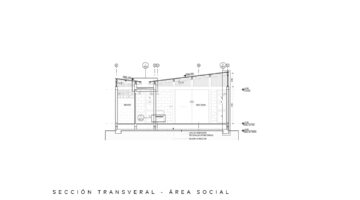

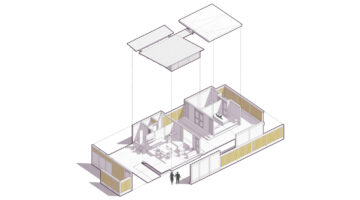

The project features a permanent housing model for displaced families: an 86m² house on a plot measuring 8m by 19m. The construction is divided into two building blocks; the social-kitchen-bathroom zone is separated from the bedrooms by an interior courtyard. Circulation is minimized to ensure the best use of the various areas. The separation of the living sector into two modules allows the house to adapt to different area and site conditions. Additionally, the design permits vertical expansion above the bedroom block or horizontal growth by adding another bedroom module if a larger plot is available.

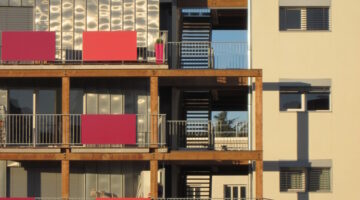

The house promotes a rural lifestyle, in touch with the outdoors, enabling families to share spaces with the community, extended family, and domestic animals. This design choice led to an open facade aesthetic, providing versatile space usage. It also supports the continuation of local lifestyles and customs, allowing them to be passed down to future generations.

The construction utilizes durable building materials that are easy to source and work with, such as concrete blocks, bamboo, and steel plate roofing. Concrete blocks were specifically used in various arrangements to create a permeable lattice that protects the inner areas while allowing natural ventilation throughout the spaces. Despite being a replicable housing model, the addition of color inside the concrete block holes offers a subtle yet strong statement, enabling families to express their personalities and fostering a stronger sense of community belonging.

This house has been designed as a self-built home, with the construction process controlled by the family or community that will reside there. It employs a traditional masonry construction method, allowing users to adjust the dimensions of different areas to the building materials, minimizing waste and reducing the construction schedule.