Situated on the Gulf of Thailand, the provincial capital of Pattani boasts a rich history as a trading hub spanning over a millennium. Formerly the nucleus of an autonomous Malay principality encompassing Yala and Narathiwat Provinces, Pattani pioneered international trade with the Portuguese in the 16th century, followed by engagements with the Japanese, Dutch, and English in the 17th century. Today, it stands as a vibrant city characterized by ancient mosques, thriving fishing communities, and bustling rubber trade, with a predominantly Malay-speaking Muslim population of approximately 45,000 individuals.

In addressing the pressing issues surrounding settlements and housing, prior approaches often imposed resettlement without considering the agency of affected communities. However, a pivotal shift occurred thanks to the intervention of a crucial organization. The Community Organizations Development Institute (CODI), operating under the Thai Government's Ministry of Social Development and Human Security, emerged as a catalyst for change. CODI's core mission revolves around empowering communities and their organizations, recognizing them as pivotal agents of transformation in both urban and rural settings. Within this narrative, two flagship programs spearheaded by CODI played a central role.

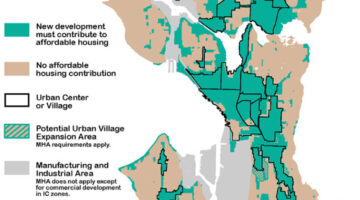

The trajectory of housing and community development in Pattani underwent a significant transformation with the intervention of the "Livable Cities" program in 2003. This initiative played a pivotal role in networking informal settlements across Pattani, fostering collaboration with civil society groups and religious organizations to address various facets of urban life, such as environmental sustainability, healthcare, and alternative energy. Noteworthy outcomes included annual canal-cleaning events and the inaugural citywide survey on urban poverty and housing challenges, revealing that approximately 30% of the city's populace (3,895 households, comprising roughly 12,500 individuals) resided in 16 informal settlements characterized by congested and dilapidated conditions, lacking secure tenure.

In addition to the Livable Cities program, the Baan Mankong Program emerged as a linchpin in CODI's repertoire, launched in 2003 to tackle housing issues confronting the nation's most economically disadvantaged citizens. This initiative directed government funds, in the form of infrastructure subsidies and soft housing loans, directly to impoverished communities, enabling them to spearhead improvements encompassing housing, environmental conditions, basic services, and tenure security. Departing from conventional approaches that delivered housing units to individual families, the Baan Mankong Program empowered Thailand's informal communities to drive a people-centric, citywide process aimed at devising comprehensive solutions to land and housing challenges in urban areas.

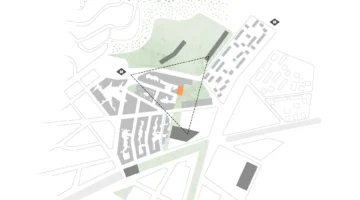

With support from the Baan Mankong Program, the community network leveraged data from the citywide survey to formulate plans for their inaugural three housing projects. The survey underscored the density of informal settlements in Pattani, highlighting the plight of joint-family households grappling with overcrowded and uncomfortable living conditions. Recognizing the challenges posed by dense settlements, the community opted to initiate resettlement projects to alleviate congestion and enhance living standards. This strategic pivot towards land readjustment was facilitated by the relatively affordable land prices in Pattani amid years of civil unrest and economic stagnation. Poo Poh emerged as the pioneering resettlement project within the city.

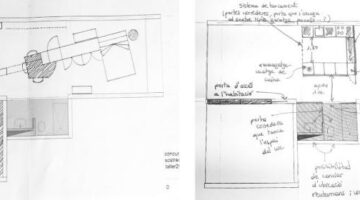

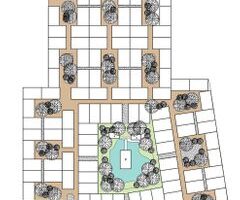

Comprising families from three overcrowded squatter settlements, the Poo Poh project witnessed the formation of a robust multi-community housing cooperative, which identified and acquired a cost-effective parcel of private land spanning 3.14 hectares for their new housing endeavor. Notably, a team of three young Thai community architects played a pivotal role in collaborating with the community to craft an aesthetically pleasing layout plan for the new development. In this collaborative process, the community's social dynamics, characterized by bonds of friendship and kinship, informed the spatial arrangement of houses clustered around communal open spaces. Central to the community layout were a mosque and expansive public garden, occupying 56% and 44% of the land, respectively, dedicated to housing plots, public spaces, roads, and community facilities. The exhaustive six-month process of developing the citywide housing strategy and spearheading the inaugural community housing project at Poo Poh engendered a sense of camaraderie and unity among the participating families through spirited planning workshops.

A distinctive aspect of the Poo Poh narrative was the segmentation of planning workshops into separate sessions for men and women, reflecting the entrenched gender roles prevalent in traditional Malay Muslim communities. Initially, joint workshops yielded limited engagement from women, prompting a strategic shift towards segregated sessions. This approach proved instrumental in amplifying women's voices, with their insights driving key aspects of the community's layout plan. Notably, women advocated for the integration of smaller "pocket parks" throughout the community to facilitate supervised play for children, challenging conventional notions proposed by men. This collaborative endeavor not only yielded a more inclusive and functional community layout but also empowered women to assert their ideas and aspirations within the broader community discourse.

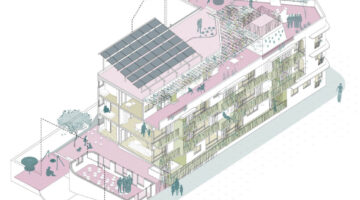

Drawing from lessons learned in prior housing projects in southern Thailand, the architects adopted a proactive approach by prioritizing the completion of infrastructure before commencing house construction. This strategic sequence not only ensured the holistic development of the community but also fostered a sense of collective ownership and camaraderie among residents. Notably, community members actively participated in house construction, organized into clusters of six to ten households, wherein they jointly managed construction activities and finances. The formation of a community committee, comprising representatives from each cluster, further facilitated decentralized decision-making and project management. Embracing diverse approaches to construction management, some clusters enlisted local contractors, while others undertook self-managed construction processes, resulting in distinct architectural expressions across the community.

Harnessing the robust social capital inherent within these communities, the project at Poo Poh exemplified the transformative potential of grassroots mobilization, fostering cohesion and cooperative spirit while securing affordable land without compromising resident agency. Moreover, the project served as a catalyst for gender empowerment, amplifying women's voices and fostering their leadership roles not only within the project but also within the broader community fabric.