Seattle “Grand Bargain” and the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program

Main objectives of the project

On July 15th, 2016, a coalition comprising 10 city officials, private developers, and advocates for affordable housing came together to sign the Seattle "Grand Bargain." This agreement, forged through unprecedented negotiations and collaboration, aimed to implement an inclusionary zoning and linkage fee program across upzoned neighborhoods in the city. Central to the Grand Bargain is the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, which mandates the incorporation of rent-restricted units for low-income households in new developments, but specifically within neighborhoods upzoned for increased density. Consequently, the Grand Bargain ensures the inclusion of affordable units in new developments while also offering development incentives to facilitate the construction of more units on a given lot, thereby mitigating the revenue loss associated with affordable housing. Through the negotiation of the Grand Bargain, the city sought to simultaneously expand the overall housing supply (by increasing density) and the availability of dedicated affordable housing for lower-income households (via mandatory inclusionary measures).

Date

- 2019: Implementation

- 2016: En proceso

Stakeholders

- City Council of Seattle

- Grand Bargain coalition

Location

Country/Region: Seattle, United States of America

Description

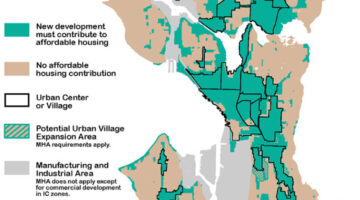

In 2016, the City Council of Seattle ratified the Grand Bargain's Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, incorporating it into city law. This program encompasses zoning code revisions to boost density across much of the city, the establishment of a mandatory inclusionary housing scheme mandating certain affordability standards for new apartment complexes, and the introduction of commercial linkage fees requiring owners of new commercial spaces to contribute funds toward constructing affordable units within the city.

The MHA program, spearheaded by then-Mayor Ed Murray in collaboration with Seattle's Housing Affordability and Livability Advisory Committee, aims to produce 6,000 affordable housing units for families at or below 60 percent of the area median income (AMI) within a decade. This initiative is anchored by 65 individual policy recommendations, with the MHA being a prominent feature. Under the MHA, the city undertakes zoning changes to boost density in commercial and multifamily residential areas and neighborhoods near transit lines. Developers are then obligated to include dedicated affordable housing within new constructions in these areas.

To offset the costs associated with incorporating affordable units into new developments and to bolster the overall housing supply, the city representatives agreed to heighten residential density in select neighborhoods in exchange for affordability requirements in new development. The MHA mandates that approximately six percent of single-family zones transition to a newly designated category termed Residential Small Lot, facilitating the construction of multiple "cottage" homes on a single lot, as well as the creation of duplexes and row houses. Additionally, some single-family zones will permit the construction of triplexes, townhomes, row houses, and three- to four-story apartment buildings.

Once an area undergoes rezoning to increase density, the Grand Bargain stipulates that residential developers constructing new units must incorporate units affordable to families at or below 60% AMI. This requirement applies solely to new constructions and/or alterations that increase the total number of units within a structure. The Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program dictates that a percentage of units constructed be rent-restricted for a minimum of 50 years. The affordability criteria range between 3-7% of units, depending on the market. Developers opting out of including affordable housing must pay the city a per square foot in-lieu fee ranging from $5 to $33, contingent on the development's size and location.

Furthermore, in neighborhoods rezoned for increased density, commercial developers are mandated to pay a linkage fee on new developments, ranging from $5 to $17 per square foot. These fees, contingent on building size and location, apply to all new constructions, expansions, or conversions from residential to commercial use. The collected linkage fees are allocated to nonprofit organizations to aid in constructing affordable housing in Seattle.

However, the path to implementing these regulations was fraught with challenges. The Mandatory Inclusionary Housing components within the MHA program only take effect once neighborhoods are upzoned, and since the program's adoption, the city's upzoning efforts have faced legal disputes and community resistance. After nearly four years of legal battles, the agreed-upon timeframe for adopting all zoning changes extended beyond the original 2017 deadline. In 2019, eventually, all the rezoning measures were enforced.

The adoption of zoning changes to boost density marks Seattle's efforts to expand its housing supply by facilitating the development of new multifamily buildings. While increased housing supply theoretically improves affordability, the significant supply deficit in high-cost cities often means initial expansions merely meet existing demand, having limited immediate impact on housing prices. By coupling increased density with mandatory inclusionary housing requirements, the policy ensures the availability of lower-cost units for low-income families and their continued affordability through legal constraints.