Social Housing - KNSM Island

Main objectives of the project

Date

- 1994: Construction

Stakeholders

- Architect: Bruno Albert

Location

Country/Region: Amsterdam, Netherlands

Diadalos, a tourist village on Kos Island, harmoniously integrates with the Aegean landscape through its adaptive architecture. Divided into private, communal, and staff zones, the design prioritizes privacy, sea views, and respect for the site's topography. By eschewing repetitive hotel patterns, it aims to authentically capture the spirit of Greek Island architecture.

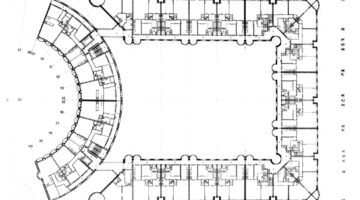

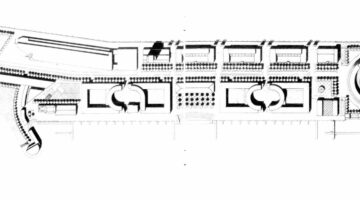

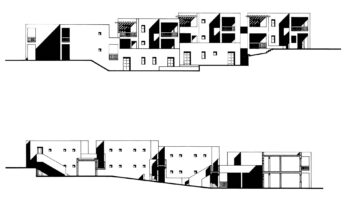

Diadalos is a tourist village designed for 1000 people and located on Kos, one of the Greek Dodecanese Islands. The village is built on a plateau at 90m. elevation overlooking the sea to the south. The main design idea was the creation of an architecture that is well adapted to the physical and cultural identity of the place. Specifically, this architecture would take advantage adapted to the physical and cultural identity of the place. Specifically, this architecture would take advantage of the landscape, respect local topography and climate, and draw inspiration from the spatial qualities of the settlements in the Aegean. With the use of the simplest formal devices and contemporary means of construction, the design seeks to recapture the spirit of the architecture of the Greek Islands, and to bring out the quality of the Aegean landscape without resorting to the use of borrowed features and figures. This design approach also helps to transform the repetitive architectural patterns that are often associated with the architecture of hotels. The resort is divided into three zones.

The first provides private accommodation, the second consist of communal facilities while the third is that of the staff accommodation. There are two residential types, namely single-bedroom or two-bedroom family units. All units have a private verandah. Rather than opt for free standing pavilions, units are linked to form single or double-storey terraces of varying configurations. The terraces define an irregular pattern of narrow pedestrian streets, covered walkways and enclosed gardens. The principles governing the layout include the provision of privacy, the creation of views to the sea and respect for the slope, contours and orientation of the site. The resulting variety of spatial relationships gives a distinct identity to each point of the arrangement.

The Marianella project (1983-1988) in Naples focused on rebuilding post-1980 earthquake. Objectives involved transforming a serial-type plan into dynamic urban interventions, creating three-floor residential blocks with courtyards. Using the French prefabrication system, it successfully addressed both housing needs and the reintegration of the outskirts.

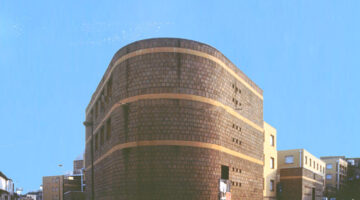

The idea behind the project for a block in Marianella, a center of the outskirts of Naples, consists in making react a type-morphological plan of serial nature, with the outline of the area, considered as a perimeter on which are projected different conditions of the context. In contact with such a outline, which is configured as an active margin, the model undergoes a series of subtractions that are proposed as architectural variations of the plan. It is subtracted so to the repetition inherent in the initial model by purchasing a geometric and plastic variability, which results in an increase of the complexity of the urban intervention.

The intervention for sixtyfour accommodation in Marianella, in the metropolitan area of Naples, was designed in 1983 and completed in 1988 after the earthquake of 1980, an event that ruined not only the historical center of the city but also the peripheral expansions. The project was thought both to be to rebuild a number of destroyed houses and to reconnect separate parts of the peripheral tissue. A urban fabric in which was spread a courtyard typology, which gave rise to complex residential units designed to accommodate families of farmers in the Neapolitan countryside. The project has taken this typological matrix, obviously transformed, proposing a series of residential blocks of three floors, organized around two types of courtyards. On the larger courtyards overlook houses with continuous balconies supported by iron pillars; the smallest include the stairs towers which, through four gangways, distribute eight apartments for each floor. The residential blocks are made with the French prefabrication system banches e tables and then plastered. The stairs have an iron structure covered with tuff. Also the portals of entry to the courts are made with tuff.

The primary objectives of the Haarlemmer Houttuinen Housing project in Amsterdam were to establish a lively and community-focused environment. Architect Hertzberger aimed to create an intimate, pedestrian-friendly street, limiting access to residents' vehicles. The design prioritized fine-tuned scale, fostering a sense of community, and incorporating distinctive architectural elements to enhance the unique character of the residential quarter.

The Haarlemmer Houttuinen Housing in Amsterdam is squeezed between a busy main road and railway to the north and Haarlemmerstraat to the south. The north block was built by Hertzberger, the one to the south by the architects Van Herk & Nagelkerke. The two blocks are separated by a pedestrian street connected to Haarlemmerstraat by two gateway buildings also designed by Van Herk.

Hertzberger s housing block has projecting piers with balconies that give rhythm to the street. Each pier marks the entrance to four maisonettes and supports the balcony of the upper two. All entrances to the dwellings are off the street and balconies and gardens overlook it. Fine-tuning of scale is

achieved by tiles in the centre of the lintels and the granite pads supporting them, and by the different sized square windows which syncopate rhythms and let in light along the ceilings where window heads have been kept closed to give intimacy within.

Hertzberger wanted the new street to be a lively community area. The street is accessible only to residents cars and delivery vehicles. With the street closed to general motorised traffic and measuring only 7 metres in width, an unusually narrow profile by modern standards, a situation is created reminiscent of the old city. Street furnishings such as lights, bicycle racks, low fencing and public benches are distributed in such a way that the passage of traffic is obstructed with only a few parked cars. Some trees are planted to form a centre halfway between the two street sections. The lower maisonettes can be entered from their tiny gardens in the street, while the upper units can be reached by external stairs to a shared landing at first floor level, where the front doors are. While the extended block on the north side of the street provides shelter from the busy main road and railway behind it, the south-side block is one storey lower to allow the sun to shine in the street. In this respect, the scheme reinstates the original function of the street as a place where local residents can meet. Streets which no longer serve exclusively as traffic thoroughfares are increasingly seen on the new housing estates and in urban renewal projects. The interests of pedestrians are being taken into consideration, and with the recognition of the woonerf as a street space in a residential area where pedestrians enjoy legal protection against traffic, they are slowly regaining their rightful ground. The decision to reserve a strip 27 metres wide fl anking the railway for traffic purposes forced Hertzberger to build up to this imposed limit of alignment. As a result there was no room on this side for back gardens, which might in fact have been permanently in the shade. Unfavourable factors such as undesirable orientation and traffic noise meant that the north side would have to accommodate the rear wall, and so automatically all emphasis came to lie on the street side which faces south. The north side has no entrances or balconies. The long, continuous rear wall forms a sort of city wall marking the limits of the residential quarter and setting it apart from the railway viaduct, the open area beyond and the harbour in the

distance. In order to involve the rear view in the architecture, the upperstorey dwellings were given bay windows. These are the only plastic features in an otherwise unarticulated wall.

Tateh Lehbib Barika is no ordinary engineer. He was born in the Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria, which are home to thousands of people displaced by conflict in Western Sahara more than 40 years ago. Growing up he experienced first-hand the harsh conditions endured in the camps, where metal roofing sheets on mud brick houses intensify the searing desert heat and often blow off during frequent sand storms.

After receiving a scholarship from the UNHCR (the UN’s refugee agency) to study renewable energy, Tateh Lehbib returned to the camps with an innovative idea to improve living conditions for his community, which had been devastated by floods. He set about building a new home for his grandmother using recycled plastic bottles filled with sand. His idea caught the attention of the local UNHCR office, which helped him secure USD$60,000 funding to build 25 more homes.

The community-led project demonstrated how readily and freely available materials could be used to build better homes, reducing refugees’ reliance on external aid and recycling problematic plastic waste. For 50 vulnerable people, the project has provided a safer, cooler place to live and for the community at large, the skills to continue building.

Like most settlements of their kind, the Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria were only ever meant to be a temporary housing solution for people displaced by erupting conflict in Western Sahara in 1975. More than 40 years after they were established, however, the camps are still home to thousands of people, many of whom have never lived anywhere else. Life in the camps is tough. Money and food are scarce and the refugees live in fragile mud houses or tents and endure harsh weather conditions.

Among the typical adobe structures used to house refugee families, are some newer buildings. They stand out because they are round rather than rectangular in shape but it is how they were constructed that is the most remarkable thing about them. The homes were built using recycled plastic bottles filled with sand and form part of an innovative project to improve the living conditions of Sahrawi refugees stuck in ‘temporary’ housing in the camps.

The project is the brainchild of Tateh Lehbib Barika, himself a Sahrawi refugee who was born and raised in the camps. He received a UNHCR (the UN’s refugee agency) scholarship to study renewable energy and returned to build the first prototype plastic bottle home for his grandmother after catastrophic flooding in 2015 destroyed 80 per cent of homes in the camp.

His idea caught the attention of the local UNHCR office in Tindouf, which provided USD$2,000 and helped secure USD$60,000 of funding from the UNHCR to build 25 plastic bottle houses across the five Sahrawi refugee camps in the province. Some refugees were originally sceptical about the initiative, wary it would take away resources from other areas like food assistance but Tateh Lehbib worked hard to raise awareness of the benefits of the project and people gradually came to accept the idea.

Construction began in November 2016 and 27 buildings (two more than expected) were completed by April 2017. The plastic bottle homes have rehoused around 50 refugees who were selected because they are on very low incomes, elderly, or have special needs or disabilities. The homes were built by the refugee community under the direction of Tateh Lehbib. The project directly employed 200 people within the camps, who in turn paid a further 1,500 people to collect and fill bottles.

Each home took about one week to build and required around 6,000 plastic bottles, which were sourced from institutions, schools, hospitals and landfill. Groups of refugees formed to gather and prepare the construction materials. One group was tasked with collecting bottles while another filled them with sand from the dunes. Once filled, a truck transported the bottles to trained masons who stacked them horizontally, filling in the gaps with sand to make a basic cylindrical structure with two windows. The interior walls were covered with a layer of earth and straw, followed by a thin layer of cement. Cement was also used to seal the exterior of the building. The homes have a double layer ceiling to reduce the level of heat coming in – vitally important in an area where temperatures regularly reach 50°C.

Tateh Lehbib’s prototype plastic bottle house cost USD$291 to build. The initial cost of the project was USD$2,400 per home due to increased labour, staffing, transportation, training, materials and tools costs. This reduced to USD$1,630 as the need for training declined. The adobe structures typically used in the camps cost around USD$582 – USD$1,160 to build.

The plastic bottle homes are smaller than their adobe counterparts, but they offer superior protection from fire, sandstorms, floods and high winds. The temperature inside a plastic bottle home is around 5ºC lower than the mud brick alternative and people living in the homes say they feel safer.

A key objective of the project was to improve not only the living conditions within the camps, but also to increase the self-sufficiency of refugees. Used plastic bottles and sand form the bulk of construction materials and can be collected free of charge from institutions, landfill or off the streets. This leaves refugees more able to pay for other materials, like cement, themselves and reduces reliance on external funding.

Even though opportunities within the camps are limited, the Sahrawi people place great value on education, learning and innovation. The project built on this pre-existing culture by running training programmes and workshops for educational centres, women’s associations and youth groups to help inspire and motivate young people to develop their ideas as Tateh Lehbib did. The Sahrawi people’s willingness to learn new skills means the knowledge needed to continue building plastic bottle homes is now embedded in the community. This increased self-sufficiency is crucial in the camps because limited economic opportunities and the harsh climate force refugees to rely heavily on international humanitarian assistance.

The important social impact of the project is coupled with its equally important environmental impact. Plastic waste is a huge and growing problem globally, but even more so in areas where there is little or no formal recycling. Plastic bottle construction recycles tonnes of plastic waste that would likely end up in landfill or in the ocean.

The durability and abundance of used plastic bottles represents a huge environmental challenge – but these qualities also make them good, low-cost building materials for communities with few resources. The plastic bottle method also uses significantly less water than building with mud bricks, preserving a precious commodity in the desert.

Plastic bottle construction is an emerging technique across Latin America and Africa. Following the success of the Sahrawi refugee project, plans are being formed to develop the method further. Tateh Lehbib intends to build a centre in the camp to investigate climatic building design with plastic bottles and hopes to attract engineers and creative architects to help improve design and efficiency, for example by replacing cement with lime and earth and improving ventilation and roof design.

Tateh Lehbib’s aim is to establish plastic bottle construction as common practice and he plans to use the method to build other much-needed resources, such as schools and health centres, in the five Sahrawi camps. He is currently involved in a research project with his professors at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria to develop further solutions.

While the UNHCR-funded project has come to an end, its impact continues to be felt by those living in the homes and also by the community at large. Plastic bottle homes may be basic but they are safe, durable and easily replicable. The self-sufficient nature of the construction method means future homes can be funded by refugees themselves (who have gained skills through participating in the project) or through individual grants. A culture of interdependence and support exists across the Sahrawi community and additional homes are already being built using the plastic bottle method, proving the initiative is sustainable without external funding.

View the full project summary here – available in English only

Homeowners living in formerly state-owned buildings are supported to work together to improve their homes through the REELIH project.

Many multi-apartment blocks in former Eastern Bloc countries Armenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia fell into widespread disrepair following mass privatisation in the early 1990s. By creating homeowner associations, residents are able to borrow collectively to carry out energy efficiency improvements to their homes. This makes heating homes more affordable, improving the health and well-being of residents.

After proving successful in Macedonia, the approach was transferred to Armenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Since all three countries face similar challenges, they all began with the principle of collective action and then went on to adapt to meet their different needs.

The project has developed connections between individuals, homeowner associations, local governments and banks. The work has helped spread awareness about energy efficiency and increased the funding available to residents to improve their buildings.

The Residential Energy in Low Income Households (REELIH) project is about the transfer of a successful approach to improving lives through improving buildings, which Habitat for Humanity began in 2009 in Macedonia. The project objective is to tackle poverty and improve the health and quality of life of low income homeowners. It is an approach which responds to a problem common across countries of the former Eastern Bloc. Before mass-privatisation occurred across the region in the 1990s, huge state-driven building programmes had provided the majority of the housing stock as multi-apartment blocks. Once ownership of these blocks was transferred to residents, the common areas of many buildings (roofs, stairs, facades) fell into disrepair as communal maintenance arrangements were not set up or not maintained by residents. As a result, thousands of buildings are at varying degrees of disrepair, with very poor insulation and sometimes dangerous structural flaws.

This project helps residents to improve their buildings by encouraging and enabling them to work together to arrange and finance energy efficiency works. The original approach was developed and trialled by Habitat for Humanity Macedonia. This provided the starting point for the REELIH project, a transfer which has been co-ordinated by the regional office of Habitat for Humanity (covering Europe, Middle East and Africa). Local partners in Armenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina have led and implemented the project on the ground, adapting specific elements to fit within the different administrative, financial, political and economic contexts of those countries.

The project, which receives funding from the United States Agency for International Development, supports individual homeowners living in multi-apartment blocks to mobilise and act as Homeowner Associations to collectively manage their buildings. These resident-led groups are able to get access to technical expertise through the project so they can make their buildings more energy efficient. As a result, residents spend less on energy and also benefit from improved air quality, which has a positive impact on people’s health.

A significant feature of the project is the work that Habitat for Humanity carries out in each country to develop financial models so the improvements can be funded. One of the ways that this is achieved is through mediation carried out between residents, the public sector and the private sector. This has really helped increase the funding available for this type of work and has made it much easier for people from different backgrounds and organisations to work together to achieve improvements for residents and the wider community.

The Residential Energy in Low Income Households (REELIH) project is co-ordinated by the Europe, Middle East and Africa branch of Habitat for Humanity International. Habitat for Humanity International is a non-governmental organisation working in 70 countries around the world. The organisation’s work is focused on ensuring that everyone has a decent place to live and on finding solutions to housing issues. This project is delivered by in-country partners: Habitat for Humanity Macedonia, Habitat for Humanity Armenia, and Enova in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The main aim of the REELIH project is to tackle poverty and improve the health and quality of life of low income homeowners living in multi-apartment buildings. The project – currently delivered in Macedonia, Armenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina but of relevance to many countries across Eurasia[1] – works by:

Through the Residential Energy Efficiency project, Habitat for Humanity demonstrates the case for public and private investment in residential energy.

The work is helping:

[1] Eurasia is a combined continental landmass of Europe and Asia. The REELIH project is applicable in particular in countries that were formerly part of the Eastern Bloc, where there has been very high subsidy and nationalisation followed by economic decline and rapid privatisation.

In many countries across Eurasia, there are large numbers of blocks of flats which were built using prefabricated units. Built between 1951-1991, this type of housing was originally state-owned and managed with high levels of subsidy. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union and former Yugoslavia, mass privatisation led to high levels of private homeownership. However, many of these buildings have fallen into disrepair and are now inefficient and expensive to heat. As countries in the region are mainly located in climate zones with cold winters, poorly heated homes affect the health and well-being of the residents, particularly those on low incomes, who also struggle with high energy costs. Heating poorly insulated buildings wastes large amounts of energy. Poorly maintained residential buildings also generate higher carbon emissions and contribute towards pollution and climate change. In this region residential buildings are the largest single consumers of energy and a major source of greenhouse gasses, especially carbon dioxide. However, the market for energy efficiency in the countries where the Residential Energy Efficiency project is working is not well developed. Also because households have been used to receive high levels of state subsidy to pay energy bills in the past, saving energy to save money is a new concept for many people.

The REELIH project acts as a facilitator and mediator between homeowners and the public and private sector so that retrofit projects can be planned, funded and delivered. This mediator role has supported the formation of new Homeowner Associations, which are organisations formed of and run by residents. Through this programme these associations have become credible recipients of both bank loans and local government subsidies, enabling them to improve their homes and buildings. This is a significant development as previously residents were not able to get access to loans to improve their blocks of flats.

Capacity building is a key feature of this project and is implemented by in-country partners: Habitat for Humanity Macedonia, Habitat for Humanity Armenia, and Enova in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Training and awareness-raising helps ensure residents know about energy efficiency and their right to adequate housing. These in-country partners support Homeowner Associations to form, to plan which home improvements they will carry out and to decide if they will manage the work themselves or through contractors.

The work of the in-country partners also extends to working with banks and local authorities. The development of a market for residential energy efficiency retrofits is a great success of the project. It has created an opportunity for low income households to access funding and has helped to attract subsidy from local government in the form of match funding for loans. With the support of the REELIH project residents in Homeowner Associations have demonstrated their ability to manage projects and loan repayments, allowing them to make real improvements to their lives. The loan repayment rate of residents working with the project is 100%, which is a significant achievement.

In addition to providing technical assistance, Habitat for Humanity funds energy audits. These audits help the organisers to decide which buildings should be targeted and also help Homeowner Associations to make informed decisions about the work they will have done.

Habitat for Humanity currently shares knowledge about residential energy efficiency via three websites, one in English, one in Armenian and one in Bosnian. These explain how the project works and take people through a step by step guide on how to make improvements in their homes and in common spaces and structures (roof, facades, stairwells) in multi-apartment buildings.

In the context of former Eastern Bloc countries, the development of a market for resident-led energy-efficiency works is ground-breaking. The history of state-control over maintenance of the housing stock, combined with a heavily subsidised energy supply means there has been very little awareness of or interest in issues like energy efficiency among residents. As a result of the work of Habitat for Humanity on residential energy efficiency, more than 3,800 individuals now live in more comfortable and efficient housing across the three countries. Retrofitting has cut energy bills for low income homeowners by up to 50%, helping to reduce poverty and tackling rising energy costs. The project supports the rights of citizens to a good home, helping residents to access the means to improve their own housing.

By 2017, the project had achieved the following:

The continued success of the work in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Armenia is now inspiring further work in Macedonia. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is funding a second phase of the project, which began in 2017 and will run until 2019.

The project has led several local governments to provide subsidies for energy efficiency interventions. In Armenia the Municipality of Yerevan has provided 40% subsidy for all energy efficiency interventions through the REELIH project. Habitat for Humanity Armenia is also working collaboratively to reform the national Armenian Housing Law, to create a better investment environment for Homeowner Associations. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, following the implementation of residential energy efficiency work by Habitat for Humanity, the Tuzla Canton local government has produced a five-year plan focusing on energy use in residential buildings. It is the first of its kind in Bosnia and will support large scale investments in residential energy efficiency across the area. It is expected this approach will spread to other areas. In addition, Habitat for Humanity is currently working on influencing the reforming of Homeowners Association laws in all three countries.

The project costs are funded jointly by Habitat for Humanity International and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Residential energy efficiency is a key part of the Habitat for Humanity International strategy for Europe and Central Asia until at least 2020 and currently US$100,000 per year is allocated to this work from the organisation’s core funding.

The costs of the energy efficiency works are covered through different routes depending on each country. Energy efficiency markets are still being developed by Habitat for Humanity and their in-country partners. In Armenia, where Habitat for Humanity has successfully set up loans for Homeowner Associations these are combined with subsidy from the local government if available.

Macedonia:

Bosnia and Herzegovina:

Armenia:

Residential Energy Efficiency for Low Income Households targets low income households affected by high energy costs, informing them about energy efficiency and providing technical support to help them manage the retrofitting of their homes. The skills people have gained through the project help them get involved in raising awareness, sharing their knowledge and concerns about energy costs as a cause of poverty and helping municipalities to further understand their residents’ needs.

By mediating between Homeowner Associations, municipalities and banks, the approach of Habitat for Humanity has improved the financial credibility and borrowing power of low income households. This is a particular accomplishment, as banks in Armenia (as in most of Eastern Europe) were previously unwilling to issue loans to Homeowner Associations. Through technical assistance and effective collaboration, the REELIH project has helped to establish new financial mechanisms, which facilitate the distribution of public funds and loans from banks directly to the Homeowner Associations. This provides an alternative to the need for each individual household in a multi-apartment building to raise their own finances. It allows a whole-building approach to energy efficiency which can be managed collectively by the residents. As the loan is also managed by a single entity (the Homeowners Association), the whole process of making improvements to buildings has also become more efficient.

Approximately 80% to 90% of energy is used during the lifetime use of a building with the remaining 10% to 20% used during construction and demolition (this also accounts for embodied energy). Retrofitting has a positive environmental impact by making buildings more energy efficient, reducing carbon dioxide emissions and the use of fossil fuels. As the number of retrofitted buildings increases, so does the positive environmental impact of the Residential Energy Efficiency project.

Retrofitting homes improves air quality and helps reduce moisture and noise, provides greater comfort and reduces the required frequency of maintenance and repair work. The retrofitting works carried out through this project can reduce the total energy consumption of these homes by up to 50%.

Specific features delivered through the programme include:

The approach of REELIH ensures materials used for retrofits provide optimal energy saving results. Different vendors are used in each building and materials are selected based on energy audits. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, most materials are produced or available locally. Some materials are imported in Armenia. Energy efficiency interventions are sometimes implemented hand-in-hand with other work on strengthening the structural stability of the buildings, improving them for future generations.

Habitat for Humanity International has placed energy efficiency within its key strategy and funding streams until 2020. As of 2017, the project has funding from USAID for at least two more years. Advocacy carried out by the project has secured commitment from a number of local governments to place energy efficiency in their budgets. This achievement has been key to the financial sustainability of this work.

The relationship building with banks is also a very important aspect. Two additional banks in Bosnia and Herzegovina have started financing window replacement and other retrofit measures, and are now interested in developing affordable residential energy efficiency products for families and Homeowner Associations. In particular, banks would like to see a Guarantee Fund to reduce the risks of loans to Homeowners Associations. This option is being explored by Habitat for Humanity, in order to expand the number of banks that would be willing to provide loans for residential energy efficiency for multi-apartment buildings.

Over time Habitat for Humanity International believe it might be possible to set up revolving loan funds so Homeowner Associations can pay for energy efficiency works without any subsidy. At the moment the market is not developed enough in any of the countries where the project is being implemented for this to happen.

Residential Energy Efficiency for Low Income Households provides practical solutions to a housing problem that negatively affects standards of living, household budgets and quality of life. The project prioritises community-building and working in partnership across different organisations and sectors, focusing on solving energy poverty for low-income families and has a real impact on residents’ lives and their homes.

Multi-sector partnership and knowledge sharing is not only carried out on the ground but also through online knowledge sharing platforms. Presently there are two national knowledge sharing website for the work in Armenia (http://taqtun.am) and in Bosnia and Herzegovina (http://topaodom.ba), and a regional website for the project at a wider level (https://getwarmhomes.org). The national platforms allow residents and stakeholders not directly involved in the project to learn about and develop their own energy efficiency improvements, and the regional one acts as an international platform to share knowledge on residential energy efficiency.

Through the REELIH project, Habitat for Humanity works with residents to set up Homeowner Associations and strengthens their ability to negotiate for improvements with municipalities and banks. Homeowner Associations and their residents are given training on energy efficiency where they can share ideas on how they can save energy and money together. The technical assistance and expertise provided empowers residents to work collaboratively and go through the process of renovation themselves. Technical support is provided for decision-making, contracting construction companies, gaining subsidies from governments and funds from other financial institutions. The training, combined with mediation, ensures Homeowner Associations are seen as credible organisations. The project also develops community relationships by supporting residents to work together.

The physical retrofits themselves lead to better health and well-being as homes are more comfortable to live in and issues of cold, dampness and air pollution are improved. Residents are able to make better use of all the space in their homes (before many would only use one room with wood or coal fires for heat). Building improvements have also led to improved community interaction by making the shared spaces (such as stairways and hallways) more useable. The infrastructure of the building (e.g. pipes, elevators, etc.) also benefitted from energy efficiency as they are now less exposed to cold and dampness and therefore need less frequent maintenance. The increased awareness and appreciation of energy efficiency has led some residents to make further improvements to their own homes, for example by fitting double glazing or investing in energy efficient appliances.

Overall the approach has tackled poverty by reducing the living costs of low income residents through energy savings.

The Residential Energy Efficiency project works in a region where energy efficient retrofits have not been well researched and are not widely understood. The project has had to work hard to prove its worth and raise awareness about the subject.

There is little clarity about homeowners’ rights and responsibilities relating to the management and maintenance of common spaces. This means there is little trust between homeowners and other partners when it comes to organising works on buildings and cost sharing. In Armenia, Habitat for Humanity has tried to overcome this by working with others on reforming the national Armenian Housing Law to improve clarity and create a better environment for cooperation and investment. Government arrangements across the region are incredibly complex, with multiple layers of administration at different levels. This presents an additional challenge with transferring the approach – not just across, but within countries.

Banks in Armenia (and across Central and Eastern Europe) cannot offer loans on buildings but ask individual residents to provide personal guarantees which can be difficult and time-consuming. The project has facilitated new lending mechanisms so loans can be made to Homeowner Associations on behalf of the whole building. This has been achieved through good communications with banks and ongoing technical assistance to residents and Homeowner Associations.

Another challenge relates to the project’s desired focus on low income households. The state programme applies an approach which awards subsidy based mostly on the state of buildings i.e. from the time of construction until today – the building has never been refurbished, it does not have thermal insulation. Surveys are conducted to determine the buildings with the highest needs. Nonetheless, most multi-apartment buildings in the area made up of mixed incomes families. As a result this means some of the households who benefit are in higher income groups. Nonetheless, one of the criteria for the building selection is that the majority of residents/ households in the building are very low income. Therefore, the project ensures that at least the largest part of the people it reaches is indeed part of their target group.

Countries in much of Eurasia are mainly located in climate zones with cold winters, so energy and heating efficiency should be a major concern for governments and residents. However, historically energy costs have been heavily subsidised so awareness about energy saving is low.

In South-East Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (unlike in Central and Eastern Europe), legal barriers exist which create additional difficulties with maintenance and new investments in multi-apartment buildings. This is further aggravated by the fact that homeowners living in multi-apartment buildings in these areas usually have lower incomes. Since the early 2000s improving energy efficiency has become an increasing priority for Central and Eastern European countries but the majority of buildings (50-70%) are still waiting for renovation so large numbers of residents are affected by high energy costs.

Habitat for Humanity International has developed several policy recommendations based on the lessons learned from the Residential Energy Efficiency for Low Income Households project:

The REELIH project is evaluated by looking at energy savings made through pre-retrofit and post-retrofit energy audits. These are carried out using an approach Habitat for Humanity developed in 2012. Energy audits are carried out by ENOVA, an environment and energy consultancy and the in-country partner for the project in Bosnia and Herzegovina and by the in-country office of Habitat for Humanity in Armenia.

Habitat for Humanity and partners have also conducted base-line surveys of the housing stock and the financial and living conditions of residents. They have looked at things like participation in Homeowner Associations, comfort levels in the home, and awareness about energy efficiency. These surveys will be repeated in the future to help understand the impact of the project.

Habitat for Humanity International started the first REELIH project in Macedonia in 2009. With the continued support of USAID, the approach was successfully transferred and has been adapted in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Armenia. Following pilot projects, a number of regional and local governments are supporting more work on residential energy efficiency. Subsidies are now being provided in five areas in the Tuzla Canton region of Bosnia and Herzegovina and in the Municipality of Yerevan in Armenia. These subsidies will match loans raised by Homeowner Associations to help pay for energy efficiency improvements. This was made possible by the work of the REELIH project.

Habitat for Humanity Armenia is also partnering with Spitak and Vayq Municipalities to work with them on energy efficiency in residential and public buildings in their areas. Their success with the REELIH project helped them to attract funding from the European Union to do this.

Visitors from the United Nations, European Union, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (GIZ), United States Agency for International Development (USAID) missions and other development agencies have been to Armenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to learn from the project. In Macedonia, Habitat for Humanity has helped to make energy efficiency a subject for students in technical high schools, providing training sessions and arranging internships.

Energy poverty and poor energy efficiency in residential buildings is a problem in many countries of the former Eastern Bloc. A great number of low income families could benefit from the REELIH approach to accessing finance and subsidy.

The REELIH work was shared in April 2017 at a conference in Brussels aimed at raising awareness and interest among EU-policymakers and developing opportunities for people to work together.

Granby 4 Streets developed out of a community group that campaigned against the demolition of houses and relocation of the community. It has successfully halted the demolition and provided a focus for the community using a creative approach. Its long term goal is to renovate all of the houses in the Granby triangle providing homes for 250 families who are either members of the original Granby community wanting to return home, or local families in housing need.

Granby 4 Streets and its predecessor community group have, for many years, kept the Granby community together. Its ultimately successful campaign to halt the demolition of houses provided a focus for the community but its approach was unconventional and creative. It focused on reclaiming empty houses and streets from dereliction and boosting the community’s pride in the area. It runs a street market that sells vintage clothes, cakes and Caribbean food. This has kept people visiting the area and has provided a visual presence for the community in the wider area and the city.

It organised community painting and community gardening. This work manifested itself in murals and artwork on the bricked up windows of empty houses and in the displays of flowers and vegetables planted in recycled containers along the length of the streets. This activity won the North West in Bloom Award in 2014.

In 2011, it successfully attracted funding from a Jersey-based social entrepreneur. This enabled the community to commission architects to set out plans for the area. These featured a number of highly innovative designs including turning one house with no roof into a glazed winter garden. The designs achieved significant media attention and won the prestigious art award the Turner Prize, in 2015.

In 2012, Granby 4 Streets successfully negotiated with the council for ten homes to be transferred to the Community Land Trust for renovation. Five have been sold and five retained for low-cost renting.

The work helped inspire other renovation projects to take place in Granby. A renovation programme by local housing association Plus Dane has seen work start on renovating 27 derelict houses. Liverpool Mutual Homes is renovating 40 houses and a local housing cooperative, Terrace 21, is soon to start renovating five houses.

In 2015, Granby 4 Streets set up Granby Workshop, a social enterprise based in Granby itself that makes household products, such as door handles and fireplaces from the waste and rubble left by the houses that were demolished. The composite material they produce has become known as Granby Rock.

In 2016, Granby 4 Streets successfully secured Arts Council funding for the Winter Gardens house. This, when built, will use two derelict houses to create a glazed communal space that they envisage will be used like a botanical garden to grow exotic plants. The building will also provide a common house for the community, have bed and breakfast accommodation and conference facilities to help generate income for Granby 4 Streets.

Aims and Objectives

Granby 4 Streets aims to bring community regeneration to the whole Granby neighbourhood, not only undoing the damage and neglect of the last forty years but retaining the best of what remained and building a better, stronger and inspiring area. Its vision statement describes creating “a thriving, vibrant, mixed community, building on the existing creativity, energy and commitment within the area”.

Its initial redevelopment brief described “retaining the generosity and flexibility of the original buildings”, and “creating a neighbourhood, which provides affordable housing; the greenest quarter in the city; is architecturally rich and includes the imaginative renovations of Victorian terraces”. Its long-term goal is to renovate all of the houses in the Granby triangle, providing homes for 250 families who are either members of the original community wanting to return home or local families in housing need.

The main issues Granby 4 Streets aims to address are:

Context

Granby is a small area of Liverpool. It comprises a series of roads of nineteenth century terraced houses, located in the Liverpool L8 area, about a mile from the city centre. It is the most ethnically diverse area of Liverpool and reportedly the home of the UK’s oldest Black community. There is evidence to suggest that a Black community has lived in this area for almost 400 years.

The community is amongst the poorest in the UK. In 2015, it was measured to be within the 1% most deprived wards in the country under the indices of deprivation. This measure considers levels of income, employment, education, health, crime, living environment and barriers to housing. The main street that runs through the area (Granby Street) was, until the early 1970s, a busy high street with grocery shops, butchers, small scale manufacturing and even a cinema. But during the 1970s, the area began to decline, residents experienced high levels of unemployment and increasing levels of poverty. Tensions in the area spilled over into 1981 with a serious civil disturbance known as the Toxteth Riots. One person died, hundreds were injured, hundreds more were arrested and many buildings were damaged or destroyed.

In the years following the riots, life in Granby became increasingly bleak. Poverty and unemployment levels became worse, more shops went out of business and empty houses began to appear as people’s perceptions of the area became more negative. Liverpool City Council’s response to these problems was highly controversial within the local community. It acquired hundreds of houses in the area for demolition. New houses were built in their place but some areas were left as vacant demolition sites. Allocation policies for the new houses were also controversial; the community perceived that they had the effect of breaking up the original community. The original houses were left standing in just four streets. But even here, most of the houses were acquired by the council and housing associations and bricked up and left vacant. Many members of the community felt that there was a policy of managed decline. Some perceived it as “special measures” (a term borrowed from the UK government’s response to failing schools) in response to, and possibly as punishment for, the 1981 riots.

Council intervention was accelerated in the early 21st Century with the introduction of the national government’s Housing Market Renewal Programme. This provided government funding for councils to deal with areas with housing in decline. During this period, more houses were acquired and bricked up and more were demolished. There was little maintenance carried out and, as a result, the remaining houses, most of which were now empty, fell into serious disrepair.

In 2010, Liverpool City Council attempted to sell the whole of Granby to a developer. There was interest and a developer was selected but after a series of challenges the procurement process eventually stalled and the contract was withdrawn. By 2011, just four of the original 14 streets remained. Most of the houses were vacant and bricked up. Just 70 residents were left in the area. Yet the residents association that had formed in the 1990s to fight the demolition of houses was still present and they sensed that an opportunity had arisen.

They became a Community Land Trust in 2011 and raised funds for refurbishment and community control.

Key Features

Community Land Trusts are locally driven, controlled and democratically accountable organisations. Membership is open to all who live or work in the defined community, including properties that the Community Land Trust does not own. Members elect a volunteer board to run the Community Land Trust on their behalf on a day to day basis. The wider community in Liverpool L8 have offered Granby 4 Streets support from 2011, with open events taking place at Granby Market.

Granby 4 Streets deliver street events, social gatherings and participative projects, e.g. a planting group, to engage the immediate and wider community. They also use their website and social media presence to update and encourage participation and deliver a digital (and hardcopy) newsletter to boost information sharing.

Granby 4 Streets has a governance structure led by a board of Trustees that comprises:

The Granby 4 Streets approach was to instigate, constitute and lead a network of projects, partnerships, and collaborations forged through longstanding negotiations with public and private stakeholders. The local authority transferred properties over to Granby 4 Streets in 2012 as an asset transfer. Steinbeck Studios, a social investor, offered an interest-free loan and funded the ‘vision document’ for the area that subsequently encouraged other partners to get involved. Steinbeck Studio provided project management in the early days and has now developed plans to redevelop homes on Ducie Street which will have a budget of several millions. Other houses in the Granby 4 Streets area are being developed by Plus Dane, LMH and Terrace 21 housing cooperative. Further financial support was obtained from Nationwide Foundation, Power To Change, Homes and Communities Agency, National Lottery, National CLT Network, Steve Biko Housing and Plus Dane Group, North West Arts Council, Trust House Foundation.

What impact has it had?

Granby 4 Streets has had an impact on Liverpool City Council’s thinking towards housing regeneration and how the council engages with local communities. There is evidence that the council has changed its approach to demolition. In 2016, another much larger area of derelict houses that was scheduled for demolition has been handed to developers for renovation.

Granby 4 Streets is cited in Liverpool Council policy as an example of community-led development. Granby 4 Streets are mentioned as proponents of good practice in terms of how residents and city officials work in partnership. They are also part of the Re: Kreators European network and they have recently presented to EU Urban Agenda ministers as proponents of good practice.

How is it funded?

Granby 4 Streets is moving towards a position of being financially sustainable. Income from rent for the houses, shops and workshop will pay the operating cost of the Community Land Trust and repayments on loans. They have calculated that every house they rent produces a surplus of £3,500 (USD $4,500) a year, which can be invested into the Community Land Trust. The set-up costs and capital costs for development work have been met by a series of grants and loans. The grants amount to £900,000 (USD $1.1 million) and are made up by:

There was also a development loan of £500,000 (USD $640,000) from Steinbeck Studio (the Jersey-based investor referred to earlier) in the project description. As Granby 4 Streets move into the next stage of their development, they are planning to use the sale of five homes to meet some of the costs. Projected income from the sale of Granby 4 Streets Community Land Trust’s five homes is £450,000 – £600,000 (USD $580,000 – USD $772,000) depending on valuations and confirmation of ‘affordability’ criteria at the point of sale.

Why is it innovative?

Granby 4 Streets is unique in the UK as a community-led regeneration of an entire neighbourhood. It is all the more remarkable because the community is amongst the poorest in the UK and has experienced perhaps the most extreme decline and dereliction seen anywhere in the UK in peacetime.

Ronnie Hughes, one of the founders and a Granby 4 Streets Trustee, said:

“What’s happening in Granby is an important prototype for northern councils, who’ve been so badly hit by the cuts, two years ago, the whole area was nearly signed over to a private developer, but now the people who live here have finally got a formal stake in the place. It’s an extraordinary achievement – and now it’s extraordinary forever”

Community Land Trusts are relatively new to the UK, and although the number is steadily growing, Granby 4 Streets is the first Community Land Trust to focus on the renovation of existing buildings. Their regeneration model is innovative internationally and has been recognised by Swiss Community-Led Housing specialists Urbamonde as an international case study.

Granby 4 Streets has embraced art as a means towards regeneration. This has seen it commission innovative designs and architecture and has encouraged creativity. This approach has led to the creation of a social enterprise and has helped engage the wider community. In addition, this has led to wider recognition, most notably by winning the 2015 Turner Prize. The Turner Prize is the UK’s most prestigious art award and is organised by the Tate Gallery. This has opened up wide media attention and has considerably boosted fundraising activities.

What is the environmental impact?

The project involves the renovation of existing buildings rather than demolition and reconstruction, making use of existing resources and maintaining original structures where possible. Granby 4 Streets has ensured that the DIY spirit from which the Community Land Trust emerged and a desire to reduce environmental impact are incorporated into their designs, e.g. the Granby Rock household appliances manufactured by Granby Workshop.

One of the first activities of the community group which predated Granby 4 Streets was community gardening. The group that continues this work, the affiliated ‘Blooming Triangle’, have renovated and created new green spaces with the local community. They continue to work with residents in maintaining the status as winners of the North West in Bloom and as finalists in Street of the Year 2015 by The Academy of Urbanism, in making Granby the greenest area in the city. Granby 4 Streets has also leased five homes to Terrace 21, an eco-cooperative, who will retrofit five homes to ‘passiv haus’ standard.

Is it financially sustainable?

Granby 4 Streets is on a path towards financial sustainability. It has a 30 year business plan which sees the organisation become fully financially sustainable by 2021. Its early work was reliant on grants for capital costs and volunteers carrying out activities to keep revenue costs to a minimum. As the Community Land Trust grows it will develop more income generating potential. Income will derive from letting houses, leasing housing to other housing associations, letting meeting-room space and, in the future, it plans to lease shop space.

Granby 4 Streets has been very successful in fundraising to support the early development and initial capital costs of the project. They have also worked with social investors to access social finance. They aim to ensure that the organisation will not be reliant on restricted income or grants and will be able to further develop using their own generated income.

What is the social impact?

Granby 4 Streets has provided a focus for community dialogue and action, in a previously disempowered and ignored community. They have created a strong sense of solidarity around housing, green spaces and community ownership. Local volunteers have been instrumental in developing the projects and have been supported to develop their own capacity in all areas of the Community Land Trust’s operation.

Residents have been given the opportunity to come together and collaborate with international artists delivering sculpture and installations. Granby Workshop, a new social enterprise making bespoke household goods on Granby Street, employs 14 young local artists/creatives, working towards delivering orders from the Turner Prize exhibition. Granby Workshop have recently showcased at the International Business Festival 2016 in Liverpool. Granby Workshop will occupy space within the planned retail units to act as the hub for local retail, social and creative enterprises bringing further economic activity.

Granby Market has continued to expand and recently moved onto the main road, Granby Street, enabling it to grow and making it more prominent and visible. Building upon previous activity they have attracted internationally recognised poets and musicians to perform and co-produce with residents an atmosphere, activities and a sense of cohesion. This contributes towards the health and wellbeing of an engaged group of residents building their own social capital. Granby 4 Streets has to date created 50 new jobs in building construction, art and community organising. This is significant in an area where unemployment remains amongst the highest in the UK, especially among young people. The refurbishment not only boosted the local economy but also offered valuable training and employment opportunities.

Barriers

Granby 4 Streets overcame a huge barrier in negotiating the transfer of ownership of houses from Liverpool City Council to the Community Land Trust. This is particularly remarkable given the historic relationship between the community and the council. Other barriers it overcame include:

They overcame these challenges by recruiting a specialist to help the board including representatives of Liverpool City Council and Steve Biko Housing Association (Liverpool’s only Black and minority ethnic (BME) housing group).

Lessons Learned

Evaluation

There is no formal project evaluation. The various funders have required regular feedback and some have commissioned external evaluations.

Recognition

Transfer

The work of Granby 4 Streets has inspired and encouraged local housing associations to acquire and renovate empty properties within Granby. Current programmes by three housing associations will see 72 houses returned to use.

Granby 4 Streets is currently working with other groups across Liverpool, e.g. Homebaked Coming Home (social enterprise for bringing empty homes into use). They share their experience of moving from activism to organisational structures. They are collating what they believe are the important methodological approaches they took at each stage to share with other working class communities in other cities

Granby 4 Streets regularly hosts visitors to share their experiences with others. For example they run workshops (60 in 2016) for planning, architectural and social science students to influence place making and creating spaces for democratic management.

This project has provided humanitarian and financial support to help communities displaced as a result of the Sri Lankan civil war to rebuild their homes. The target is to fund and build 50,000 houses, for an estimated total of 225,000 people. The majority of the houses, 44,000 are self-build, 4,000 will be built by plantation workers, while only 1,000 are to be built by contractors.

Following the prolonged civil war in Sri Lanka from 1983 to 2009, the Government of India took the decision to provide humanitarian and financial support to the Government and people of Sri Lanka to help them recover from the trauma of war. In total, the Government of India is supporting a number of self-help housing rehabilitation/development programmes costing over USD $240 million. Some of this funding is a grant, for example the funding for the 50,000 Houses of War Victims project, and some takes the form of long-term loan assistance.

For this project financial assistance and organisational support has been provided to help internally displaced people to construct their own homes. The target is to fund and build 50,000 houses, for an estimated total of 225,000 people. The majority of the houses, 44,000 are self-build, 4,000 will be built by plantation workers. One thousand houses were constructed by commercial contractors before the owner driven approach was introduced as a more suitable solution. The focus on self-build is designed to give people a real say in their own housing solutions.

The programme focuses on internally displaced people in dispersed, rural areas of Northern, Eastern, Central and Uva provinces of Sri Lanka. The basis of the programme is that people are enabled to return to land and property which they owned and lived in prior to the war. In effect, this means that some families are moving back to the area they left in 2009 or before.

The houses that are developed are on average 550 ft2 in size, so relatively large compared to those often built as part of rehabilitation projects. The home owners are able to make decisions on the design, materials used, size of the house and whether they wish to add in their own savings or loans to include specific features or make the house larger.

Since the construction work started in 2012, forty-five thousand, two hundred houses of the 50,000 target have been completed. The houses are built on existing sites in villages or new sites provided by the Government of Sri Lanka.

Aims and Objectives

The main aim of the project is to deliver homes for internally displaced people in a quick and sustainable way. These people are the direct victims of the conflict: those who lost homes, property, assets, family members, livelihoods, income and social networks. The other beneficiaries are the plantation workers living in poor housing and environmental conditions for whom 4,000 houses are being constructed.

Though this project is confined to the provision of houses, it has laid a foundation for a people-sensitive and community-driven approach to development. Housing is the crucial first phase in a long-term rehabilitation process that must be eventually followed up by:

Context

The Sri Lankan civil war lasted 26 years and left large numbers of houses and public infrastructure damaged or destroyed. Around 160,000 houses were affected in the Northern Province alone. After such a long conflict, community life was shattered with networks and relationships broken down. The economy and governance structures were in crisis. Displaced families returning to their places of origin were housed in temporary shelters, constructed by the Sri Lankan Government, humanitarian agencies or families themselves. Families survived with minimal security and scant protection from the elements. People were living in widely dispersed sites, many in forests with poor road connectivity, no electricity or other services.

This project is working in the districts of Jaffna, Kilinochchi, Mullaithivu, Vavuniya and Mannar in the North and Batticaloa and Trincomalee districts in the East, which were areas of considerable conflict during the war and the most severely affected in terms of human and material losses: houses, physical and social infrastructure, transport, industry, commerce, business establishments, jobs and livelihoods were either destroyed or severely damaged.

Key Features

The focus on self-build housing changed the complexion of the reconstruction process and has planted seeds for people-led recovery.

Adopting an owner-driven approach meant:

The potential beneficiaries applied for inclusion in the project and the severity of need was used to for selecting those who would get involved and prioritised:

Both the beneficiary selection and grievance redressal systems involved the entire community, as the approved lists were displayed in public places for everyone’s information and intervention. Debate and discussion around the list and the openness of the system to listen to every view and opinion made the process participatory and democratic.

Besides officers of the Sri Lankan Government the four partner agencies, namely UN-Habitat, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Habitat for Humanity and National Housing Development Authority provide assistance in the identification and selection of the beneficiaries. The project wanted to serve the most severely affected people in the greatest of need.

The key features of the project can be summarised as:

What impact has it had?

The project is still being completed and therefore it is a little early to expect it to influence policy or institutional change. However, this model of facilitation by partner agencies has been presented to the Government of India as a way to improve owner participation and the quality of construction in the national housing programme for rural communities.

The project goes beyond accepting the conflict/disaster victim communities’ right to housing and rehabilitation. It provides housing and infrastructure and it provides houses that are better and bigger than the minimum size prescribed and does so in a manner that builds community capacity to meet other aspects of full recovery challenge now.

How is it funded?

The Government of India provided a grant of LKR 34.8 million (USD $240 million) for this project.

Phase I for one thousand houses constructed by contractors at a cost of LKR 1.4 million (USD $10 million).

Phase II for the construction and repair of 45,000 houses had an outlay of LKR 33.4 million (USD $240 million) to cover the following:

The cost of land, physical infrastructure and social amenities is met by the Government of Sri Lanka

The houses, both repaired and newly constructed, are ownership assets of the 50,000 families and so the costs of maintenance are the responsibility of the owners. The cost of maintenance of the physical and social infrastructure is borne by the Government of Sri Lanka through its departmental or development agencies.

Why is it innovative?

Self-build construction is not new in Sri Lanka. Houses had been constructed and projects had been implemented using that principle after the 2004 tsunami. What is new and an institutional innovation is the introduction of the partner agency as part of the organisational design for implementation. The facilitation role undertaken by the likes of UN-Habitat, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Habitat for Humanity and the National Housing Development Authority is new to Sri Lanka and the support and direction provided by these organisations has been key to the acceptance of the project by target communities and to the success of the project as a whole.

Innovation within a post conflict rehabilitation context can be expressed as follows:

Though a majority of the home builders have used conventional materials and techniques, some innovations have been introduced by the partner agencies. A visit was arranged to Kerala, Gujarat and Maharashtra in India for staff from partner agencies so that they could see innovative materials, projects and experiments. Fifteen engineers and supervisors participated and tried many options such as rat-trap bonds for masonry; filler slabs for roofs; twin-pit systems instead of conventional soak-pit methods for latrines and cement soil blocks in place of bricks were tried out on experimental basis.

What is the environmental impact?

The choice of materials which are locally produced and available, usable by local craftsmen, easily repairable or replaceable, low cost and requiring low maintenance has been the main philosophy of the project. Home builders have been exposed to alternative materials, construction techniques and explained economic, environmental and social benefits. However, the project has not imposed any material or technique or technology on the home builders and the choice always remains with them.

In terms of the resilience of housing to natural disasters, several factors have been incorporated:

In addition, some of the partner agencies have developed features which help improve the wider environment. UN-Habitat has raised special funds for tree planting and developed a community supported tree planting program in new settlements.

Is it financially sustainable?

In terms of overall housing need in providing 50,000 houses, this project has met a quarter of the needs of the Sri Lankan people. The additional housing required and also the subsequent phase of this programme (focused on economic development and wider infrastructure) will fall to the Government of Sri Lanka to fund.

To reduce future costs for home owners care has been taken to produce houses of:

What is the social impact?

The ‘owner-driven’ approach of this project has greater objectives than just the reduction in cost of construction through owner’s unskilled self-help labour contribution. The participatory/consultative approach is meant to see them as ‘owners’ and ’clients’ (as opposed to recipients of grants) and gives them decision making power. It has been noted that the system of self-build and decision making has not only improved the construction of the houses but has played a significant role in restoring people’s self-worth and cultivated a sense of dignity.

Housing is the first and the key input in the long term and multi-faceted rehabilitation and recovery process for the individuals and the communities. In the area of physical rehabilitation and full scale recovery much remains to be done in terms of development of infrastructure – physical and social, for example, the restoration of livelihoods, creation of jobs and employment generation. It is in that context that the social capital built through a participatory house building process will be advantageous. Over a year long process of engagement in decision making, responsibility sharing, problem solving, conflict resolving, finance management, delivering and achieving has left a more determined, confident and responsible individual and citizen.

Barriers

Initially the programme met many barriers:

These barriers have been addressed by the project partners by:

Lessons Learned

The success of the programme has been attributed to:

Evaluation

The houses have only recently been occupied and the program is still under implementation so no final assessment has been undertaken. However, a range of indicators have been considered during the development of the programme:

Discussions have started with local universities, NGOs, international development agencies and communities to undertake feedback studies on the impact of the owner-driven, self-help approach to construction.

Recognition

This is the first time that this project has been submitted for any award. However, the model has been acknowledged by the development partners in Sri Lanka including Diplomatic/UN Missions, INGOs and the Government of Sri Lanka.

Transfer

The model has already been adopted by the Indian government-owned Housing and Urban Development Corporation’s Committee on Rejuvenation and Strengthening of Building Centres Network, which is examining ways to revitalise the network of building centres in the country in order to support large-scale construction programmes. The approach of confidence building, motivating, initiative-taking and empowering the owners has been adopted for the 4,000 plantation workers’ houses, which are yet to be built. Beneficiaries and plantation companies have endorsed the approach. These houses were originally going to be constructed by contractors.

The positive outcome of the project approach, both in the well-constructed houses and in human terms (i.e. confident, self-respecting, initiative-taking communities) suggests the replication potential, not only in post-disaster reconstruction scenarios but also in normal circumstances where the clients are disadvantaged in some way.

This eco-sanitation project enables marginalised communities in urban informal settlements to access basic services through the community-led provision of bio-centres, which provide toilets and bathrooms and an additional floor for housing, offices, business spaces, etc. The community development process enables people to gain skills and a strong sense of ownership and to deliver an eco-sanitation facility that fits local needs. To date, over 70 bio-sanitation facilities have been put in place across Kenya.

Through this eco-sanitation project, the Umande Trust seeks to involve marginalised communities living in urban informal settlements in accessing basic services through community-led provision of bio-centres. The Trust facilitates community participation and provides training and support to enable informal settlers to lead on the planning, design and management of the facilities. This community development process enables people to gain skills and a strong sense of ownership, and to deliver an eco-sanitation facility that fits local needs.

The facility is made up of a bio-sanitation facility (toilets, bathrooms) with an additional floor for housing, offices, business spaces, etc. The bio-gas generated from the facility provides clean energy for cooking and lighting.

The project started in January 2013 and, to date, has successfully put in place over 70 bio-sanitation facilities across Kenya in five counties: Nairobi (in Mukuru, Kibera, Mathare, Korogocho and Kibagare settlements), Kisumu, Nakuru, Embu and Kirinyaga. Five of the completed facilities also include a total of 23 housing units. These facilities are spread across schools and other institutions, urban informal settlements and market places around the country. The projects have so far worked with 70 self-help groups or community-based organisations and delivered facilities that each receive around 500 people per day.

Aims and Objectives

The overall objective of this particular project is to increase the use of eco-friendly sanitation technologies and their by-products for improved health and livelihoods in the informal settlements in Kenya by means of improved management of human waste, increased access to sanitation services and safe water through the construction of the sanitation facilities (bio-centres).

The initiative responds to issues that communities in informal settlements face in terms of lack of access to sanitation, inadequate housing and water crisis. Beneficiaries include:

Currently, only the occupiers of the building can make use of the bio-products. However, in the next five years Umande Trust plans to have a factory that can process and store the bio-gas in cylinders and the manure in containers. This will serve residents, households and small-scale businesses within the informal settlements.

Context

Around Kenya, houses in informal settlements are characterised by low-lying, non-permanent structures constructed of walls and roofs made of mud or iron sheet and concrete floors. These houses generally lack access to toilets, bathrooms, sewerage systems and proper lighting. As urban growth increases, the quality of the environment across informal settlements is deteriorating at an alarming rate. This is manifested in the loss of bio-diversity, the accumulation of solid waste and faecal matter, the increasing prevalence of disease and other indicators of low quality environmental factors. The geographical location of many informal settlements, which are often found in valleys, high risk zones etc., makes them difficult to access, leading to complex water and sanitation issues.

The limited access to sanitation means that residents have to use inadequate methods for waste disposal such as buckets, flying toilets[1] or open defecation. This hygiene disaster has created numerous disease outbreaks of cholera, dysentery and diarrhea. Various measures have been taken to help improve access to water and sanitation; such as communal pit latrines, portable toilets etc., but had not been able to tackle the scale and depth of the problem.

The eco-sanitation facilities (bio-centres) are designed by the community group to address the issues that the community faces in accessing decent sanitation, and other needs such as the lack of housing and multifunctional spaces.

[1] Use of plastic bags as toilets, which then get ‘flung’ away – hence the term ‘flying toilets’

Key Features

Umande Trust believes in community-led processes based on the full and effective participation of all stakeholders. The scope of activities within the programme include initial selection of the community group who will lead the delivery of the construction, research to determine the scale and location of the toilets, training the group on hygiene promotion, financial literacy and governance and the construction of the sanitation facility.

Initially, the Trust sends out a call for community groups to apply to manage the bio-centres, using posters placed within the informal settlements or via key stakeholders such as village elders, ward-level local government officers or members of the county assembly as a way of reaching community based groups.

The characteristics of a community group suitable to lead this work include:

Once a group has been chosen, a design session is held in which they give inputs into what they want the building to look like as part of developing a work plan. The activities start with a survey to determine the number of users and their attitudes to fees for using the services. This involves quantifying the number of households in the informal settlement to establish potential demand to guide the design process.