Project Description

The programme helps people from low-income communities become homeowners in the district of Anantapur and surrounding areas in the state of Andhra Pradesh. The main groups supported by the programme are members of the Dalit castes (this term refers to the lowest castes in the traditional Indian caste system), scheduled castes and tribes (these are castes and tribes officially designated as disadvantaged by the Indian government) and people with disabilities in these communities. Rural Development Trust is particularly focused on supporting and empowering women.

It does this through providing women with a part self-build programme to help them build their own house. It helps them with formalising ownership of the land, and provides specialist skills such as masonry and carpentry. Women and their families are expected to contribute about 150 days labour to the building work on their own houses as well as communal buildings such as schools and community centres. The philosophy of the programme is that becoming a homeowner improves women’s social status and helps them out of poverty. The project ensures that the benefit is long term. Homes cannot be mortgaged or sold for a minimum period of 25 years after construction.

The project currently operates in 3,589 villages. By March 2015, 61,895 houses had been built including 2,661 for people with disabilities. From 2015-2016, there were 5,303 houses built in total. This included 82 for people with disabilities, 400 in collaboration with the government, and 2,496 for people of the Chenchu tribe of the Srilailam area. This is an indigenous group, considered a scheduled tribe, living in dense forest areas. To date, approximately 380,000 family members have benefited. The programme is ongoing and expanding.

Aims and Objectives

The Community Habitat Programme sits within the wider mission of the organisation, which is about building the capacity of disadvantaged communities through holistic development. It is part of a range of programmes designed to support this mission which include education (the provision of schools catering for special educational needs and activities to support culture and sport); health and affordable healthcare via the provision of hospitals; self-help groups including training and savings groups; targeted working with tribes; and ecology initiatives to support farmers (including water harvesting and introducing alternative energy).

The Rural Development Trust recognises housing is central to ensuring a better quality of life. The main aim of the Community Habitat Programme is to provide permanent housing for marginalised people living in poverty in rural India. They aim to improve people’s living conditions by:

- Improving access to education, healthcare and other facilities through better infrastructure.

- Empowering women by supporting them to own their home.

- Promoting equality of marginalised groups by providing access to secure housing.

- Improving resilience to natural disasters.

- Ensuring families have easy access to water to improve sanitation and hygiene.

Context

The Indian population is still predominately rural. According to the World Bank 67% of the population lived in rural areas in 2016. According to the National Family Health Survey, concluded by the Indian government, only 19% of the rural population lives in pucca (strong) houses, while the remaining live in kaccha (weak) and semi-pucca houses with mud walls and thatched roofs. Eighty-seven per cent of homes in the villages do not have toilet facilities. Cooking is usually done inside the house under inadequate ventilation with biomass such as dried cow-dung, fire wood, dry weeds or crop residue

According to the 2011 census, about 45% of people in the state of Andhra Pradesh live in one room houses. Sixty-three per cent of these homes house families of four or more. There are massive fluctuations in the cost of construction materials and they are not always available. This means that low-income people cannot afford the cost of a home and depend on government housing. Distances to rural areas and poor roads mean that information, funds and materials are not always easily available. This means that villagers are left vulnerable and unable to access government schemes they are eligible for. Rural Development Trust acts as an intermediary by bringing all stakeholders together to ensure that rural communities are in a position to get the support they need.

According to RDT, Anantapur district has long been a difficult place to live in. It is a land-locked district with patchy rainfall and an arid landscape. Large farm-holders have long enjoyed a feudal hold over lower-caste tenant farmers. Bonded labour is common (this is a form of slavery created by indebtedness repaid by labour or services).

Key Features

The programme is part of a vast range of activities to help people living in poverty in rural areas who are disadvantaged. Women in particular are empowered and supported to become the owners of a plot of land. Rural Development Trust then helps them build a house on that plot. To be eligible for housing families must be permanent residents of the village, not have a permanent home, and already own a plot of land (or have an ownership right that can be formalised) and be involved in community groups. People who are not currently living in government owned housing are prioritised.

Not all of the households the programme helps are existing landowners. If there are government programmes that allocate plots to people, the programme helps them through this process. For example, they supported households in accessing land through the Indira Awaas Yogana programme by the Ministry of Rural Development. If land has not been allocated, the Rural Development Trust supports and encourages collective action through self-help groups, helping marginalised women to assert their right to housing.

For those families that already own land the programme helps women with the formalities of amending the deeds into the women’s name.

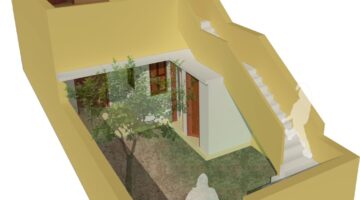

The houses consist of two rooms and a veranda. They are designed to be functional, structurally safe and fit for purpose. All have an electricity supply, and are designed to be well ventilated. For water, Rural Development Trust constructs wells in villages which don’t already have them or where they are not working. Homes in flood prone areas are built on a plinth so that they are at less risk of being flooded.

People with disabilities are a priority for housing as they are considered the most vulnerable amongst all communities. Homes are designed specifically to meet their needs. A ramp with a bathroom and toilet is provided due to limited mobility for fetching water. A village must have a Vikalangula Sangham (a collective group for people with disabilities) to be able to qualify for disability-specific housing. The Sangham nominates people who are eligible for the programme.

Rural Development Trust staff members are responsible for ensuring the success of the project. They make sure that families take part in building work to understand the value of their home and create a sense of ownership. They teach the community that providing homes in a village is part of a wider commitment to improve living standards for vulnerable groups. They also encourage women to join Sanghams (collectives) to become more integrated in the community.

After people have been selected to be part of the programme, they are divided into sub-groups of five to ten families. This speeds up the construction process as people can help each other, and also creates a healthy competition between groups. The work carried out by families includes clearing sites and digging foundations. They are also included in selecting masons and choosing locally available materials such as metal, stone and wood. Costs are finalised with Rural Development Trust staff to ensure financial transparency and accountability.

Where ever possible, construction work is carried out in partnership with government. Government agencies provide infrastructure such as water, electricity and road improvements to coincide with construction of new houses built by the Rural Development Trust.

What impact has it had?

Overall the programme has provided 67,189 people from poor rural communities with permanent shelter. It has also leveraged the opportunities provided by the Swachh Bharat Mission[1] to build 6,116 individual household latrines. This work will continue and enable Rural Development Trust to provide a further 40,000 bathrooms with toilets.

In total, Rural Development Trust have built 2,661 homes built for people with disabilities. Since 2006, seven projects have been undertaken to help communities being displaced or affected because of dam or road construction. These projects include ensuring the communities are properly connected to infrastructure and services like power and water.

In their 2015-16 annual report for the Habitat Programme the Trust reported 5,303 homes were built:

- 4,821 houses for women in disadvantaged rural communities, including 2,496 for the Chenchu tribal of the Srilailam area.

- 82 houses for people with disabilities.

- 400 houses by drawing funding from government programmes.

The work of the Rural Development Trust has generated substantial broader impacts to help many marginalised and disadvantaged groups out of poverty[2].

[1] The Swachh Bharat mission was launched by the Government of India in October 2014. The objectives of Swachh Bharat are to clean the streets, roads and infrastructure of the country’s cities and towns, and to reduce or eliminate open defecation through the construction of individual, cluster and community toilets. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swachh_Bharat_Abhiyan)

[2] See examples of success stories on the website, http://rdtfvf.org/freedom-us-people/ (how RDT helped members of the Amaragiri chenchu tribe escape bonded labour), http://rdtfvf.org/from-poverty-to-progress/ (how RDT supported a young boy from a poor rural household to qualify as a doctor)

How is it funded?

Rural Development Trust is a charitable foundation that sources most of its income from individual and corporate donations. It sources a large proportion of its fundraising from Spain where the organisation is known as Fundación Vicente Ferrer. There is also a fundraising team based in India to raise money from individuals, public and private organisations. The organisation has a highly effective fundraising operation raising over US$39,000,000 in 2015-16 from grants & donations: 119,923,419 rupees (US$1,858,064) in donations and 2,406,480,420 Rupees (US$37,285,430) in grants.

The organisation decides how many houses it will build each year as part of its annual business planning process. A budget is allocated from the central funds of the organisation to pay for it. Where possible the Trust also builds homes through government housing programmes, coordinating with the relevant departments.

On average, Rural Development Trust constructs 4,000 houses per year using a combination of its own funding and government funding (either attached to programmes guaranteeing access to land, or programmes benefitting scheduled castes or tribes) In 2015-16, 5,303 houses were built with a budget of around 500,000,000 rupees (US$7,723,800) (which is the approximate spending on the programme per year). The average cost of building is 160,000 rupees (US$2,472) per house, including materials and labour, although there are big fluctuations. The labour contributed by residents saves around 30-35% of this cost – therefore the actual costs are of around 105,000 rupees (US$1,630). The community is also directly involved in bargaining and purchasing of materials for building. All financial costs are met by Rural Development Trust and will continue to be in the future.

Why is it innovative?

By campaigning for women’s ownership of land and homes, their work helps empower women in marginalised communities. As well as increasing their social standing in the community, it provides women with a permanent asset and secure home. Every Community Development Committee (CDC), a group of villagers who supervise the housing programme, must have a minimum of 50% female members. This means it is a requirement to have at least an equal number of female voices in charge of local projects.

The Housing Construction Committee is made up of housing representatives and members of CDCs. Its role is to ensure the project is being carried out effectively. To enable them to do this, they receive various forms of training. For example, they are taught about technical specifications and housing design, quality, pricing and storing of construction materials, project cycle management, etc. The approach is designed to be delivered directly to beneficiaries without the need for middlemen. A number of staff members are involved at many different levels. For example, there is a national technical director, directors and engineers at a regional level, team leaders, engineers, accountants and community organisers at a local level. There is a central office which provides overall coordination and support.

During construction there may be a saving on the cost of a specific material due to collective bargaining power. This means the actual expenditure would be less than estimated. This saving can then be put towards the purchase of another item, which may have increased in cost due to massive fluctuations in prices. If there is in fact an overall saving on the estimated cost of the homes, this is reinvested back into the community as a whole.

What is the environmental impact?

When building houses, Rural Development Trust considers the risk of flooding, and the risk of contamination of the local water supply. Water is important both during construction and for the proper maintenance of bathrooms and toilets. An objective of the programme is to end open defecation. In order to achieve this toilets are constructed. The Trust also provides education programmes to support the health of the communities and raise awareness. Ways to reduce water usage have been introduced. These include modern irrigation systems and collecting rainwater.

Locally available materials such as stone and sand are used for building. These have low embodied energy because of shorter transport costs and lower levels of manufacturing. Earth bricks were used previously but these had to be fired and are now no longer used. Now cement bricks are used to avoid this. Residents are encouraged to get solar lamps to generate power. In areas with no electricity these are provided by Rural Development Trust.

Rural Development Trust has built 2,845 homes in areas affected by natural disasters. In these areas, homes are elevated 45cm above the ground to protect against flash floods and from heavy rain in the monsoon season. It also protects homes from snakes and scorpions.

Is it financially sustainable?

Rural Development Trust is a charitable foundation that sources most of its income from individual and corporate donations. It sources a large proportion of its fundraising from Spain where the organisation is known as Fundación Vicente Ferrer. The organisation has a highly effective fundraising operation raising over US$39,000,000 in 2015-16 from grants and donations.

The organisation decides how many houses it will build each year as part of its annual business planning process. A budget is allocated from the central funds of the organisation to pay for it.

Once the houses are built, the model is highly sustainable for the residents. There are no rent or mortgage costs once the home is completed. Some residents have developed skills through the building work, and have become skilled masons through practice. They are now able to make a living from masonry work.

What is the social impact?

Each village has a Community Development Committee (CDC), which is made up of representatives from the village. Each CDC must have a minimum of 50% female members. These groups are involved in selecting families eligible for the housing programme. They help in choosing construction materials and negotiate their cost. They ensure that families take part in the building work, monitor day-to-day progress of construction and resolve any problems. They also regularly update village registers to ensure financial transparency. This means that the CDC is mutually responsible for the success of the housing programme, along with staff.

Structural changes such as these have contributed to better hygiene amongst the wider community

People are encouraged to be involved in the project to create a strong community. It is more likely that people will maintain their community facilities if they feel a strong sense of ownership and pride in the work that has been done.

Barriers

Barriers to delivering homes in rural communities can include:

- Scarcity of construction materials and high fluctuations costs of materials.

- Scarcity of skilled workers.Government Policies e.g. in initiatives such as the Indira Awaas Yogana programme, the government pays a small amount of around rupees 40,000 (US$620) after deducting applicable taxes to the beneficiary with the assumption that this is enough to build a house. Nonetheless, given the current market prices, this is largely insufficient (accounts for only about 25% of costs).

Barriers have been overcome by:

- Encouraging labourers to get employment through the National Employment Guarantee Scheme. The scheme aims to enhance job security in rural areas by providing at least 100 days of paid employment per year to households whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work.

- Creating a revolving fund to support women to help them generate income and compensate for the financial shortcomings of government programmes

Lessons Learned

- The programme has found that house construction alone is insufficient to build the resilience of the community. It has increased its focus on “inclusive growth” in villages which involves construction of more community buildings such as schools, libraries, and school grounds for sports.

- The programme has changed its approach to bathrooms and toilets in order to overcome open defecation. Previously shared toilets were used, but now houses incorporate their own toilet and bathroom.

- Traditional toilets proved impractical in areas facing severe water shortages. Rural Development Trust has begun installing dry toilets (a toilet which does not use water to flush but treats waste through composting).

- Involving residents in construction creates a feeling of ownership and pride.

Evaluation

The Rural Development Trust has an independent Monitoring and Evaluation arm (M&E) which carries out evaluations and impact assessments. Nonetheless, funders also occasionally demand an independent audit of the project.

Evaluation of the project has shown:

- Housing has enhanced the social status of marginalised communities.

- Technical expertise has ensured quality housing.

- A women-centred approach has encouraged women to be involved.

- There is a feeling of ownership amongst residents.

- Awareness of sanitation and hygiene has led to proper maintenance of bathrooms and toilets.

- Water is a key issue in housing and problems with water should be addressed.

- Housing is a major factor in empowering rural communities.

- The specific needs of disabled people were addressed in the building design which has provided great improvements in daily living.

Recognition

Rural Development Trust has received numerous awards for its housing programme, as well as for its integrated approach to development. Many of the awards cover the wider work of the organisation. Some examples of recognition of this programme are:

- Member of the Government of Andhra Pradesh – NGO Coordinating Committee for Rural and Urban Development.

- ‘Population Control Board’ Award by the State of Andhra Pradesh for the quality work done in Rural Development Trust hospitals.

- Member of the Commission for the Eradication of Poverty, Government of Andhra Pradesh.

Transfer

Rural Development Trust has significantly scaled up the programme from its early beginnings. Its output is increasing each year. The programme has already reached over 3,500 villages in two states of India. They are working to expand their coverage further.

Although there is no direct transfer to other organisations, the programme would like to create a network with other research organisations or non-governmental organisations working on similar housing projects. It would like to share its experience of cost-effective housing with others.