Habitat for Humanity Egypte (HFHE)

Main objectives of the project

Since 1989, Habitat for Humanity Egypte (HFHE) has effectively assisted more than 25,000 impoverished households across selected rural and urban areas by offering interest-free loans for essential housing improvements, renovations, and new construction projects. Within Egypt's developing microfinance sector, HFHE stands as the sole provider of micro loans dedicated solely to housing-related endeavors. These short-term loans, averaging EGP 7,000 (US$ 890) each, are repayable over a 24-30 month period in monthly installments, with the first payment due a month after loan receipt. All loans are structured without profit or interest, but include an inflation adjustment to safeguard HFHE's loan capital value and support the operational costs of partnering NGOs.

Date

- 1998: En proceso

Stakeholders

- Habitat for Humanity

Location

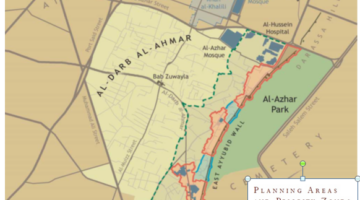

Country/Region: Cairo, Egypt

Description

In Northern Africa, addressing the housing sector's challenges, particularly in financing projects for low and medium-income families, remains a significant issue. Despite having homes and support from NGOs, non-profits, or the government, many struggle to secure financial assistance for refurbishment or reconstruction while maintaining their autonomy. This is where Habitat for Humanity Egypt (HFHE) steps in. Habitat for Humanity is an International NGO. Yet, has a great implementation in Egypt. Since 1989, HFHE has effectively aided over 25,000 impoverished households across selected rural and urban communities by providing "no-profit, no-interest" loans for essential housing improvements, renovations, and replacement home construction.

HFHE functions as a national intermediary NGO, abstaining from directly disbursing loans. Instead, it offers loan capital, technical assistance, training, and oversight to partner NGOs and participating community-based organizations (CBOs), which assume direct responsibility for loan management. In FY2015 alone, this decentralized network of independent non-profit entities disbursed 2,393 HFHE loans, totaling EGP 20.2 million ($2.6 million USD) to needy families in 22 rural and provincial urban communities. The process is straightforward: HFHE allocates loan capital exclusively for housing microloans to its NGO partners, who, in turn, supervise local CBOs and loan committees to administer and oversee these loans. HFHE provides training and technical support to partner NGO staff responsible for these loans, as well as to participating CBOs and loan committee members in each community.

HFHE operates autonomously from the financial system. It has never sought loan capital from Egyptian banks and maintains no microfinance relationship with local banks. Egyptian banks typically refrain from extending banking or home improvement loans to HFHE's clientele—poor and low-income households—due to their unregistered homes and lack of property ownership documents. Consequently, Egyptian banks and HFHE are not seen as direct competitors, with HFHE clients eschewing Egyptian banks as alternative lenders. Meanwhile, the annual interest rates on personal loans from Egyptian banks, ranging between 10.5% and 12.5% since 2008, far exceed the 7% annual inflation adjustment applied to HFHE microloans.

The lending approach of HFHE consists of three main strategies: normal lending, wholesale lending, and home improvements for the poorest households. In normal lending, HFHE partners with NGOs for an indefinite period, sharing the risk of bad loans. The loans have no end-date, with an average size of EGP 7000. In wholesale lending, a pilot initiative with CEOSS, loans are disbursed for five years, with the partner NGO bearing all risk. Higher fees are charged, and the repayment period is defined. Both approaches have identical loan terms and conditions. Home improvements for the poorest households are charitable initiatives, targeting those unable to repay loans. The improvements aim to enhance living conditions and are funded through various means, including donations and partner NGO commitments.

The majority of borrowers additionally benefit from complimentary engineering technical services for their intended home improvements. Notably, the expense is not incorporated into the loan amount for repayment; instead, HFHE covers the entire cost of these engineering services from its own budget. Skilled and trained engineering graduates are engaged on a part-time basis to support CBOs and loan applicants in defining construction requirements, creating engineering designs (if necessary), assessing actual costs for planned home renovations and new construction, and inspecting completed projects. These engineering graduates are engaged on an annual basis, with HFHE currently maintaining contracts with four part-time engineering graduates.

HFHE imposes specific criteria for borrower selection, categorized into three areas: the need for adequate shelter, ability to repay the loan, and willingness to partner. Eligible borrowers must be homeowners within the community, with no discrimination based on demographics. To qualify, households must lack adequate shelter, demonstrate low income, and exhibit financial stability. They should also display willingness to contribute to home improvement costs and participate in related activities. The organization gives priority to vulnerable groups like orphaned children, widowed women with dependents, and married couples with dependents.

The loan application process of HFHE involves several steps. First, applicants submit a one-page Loan Request Form to the CBO loan committee, providing personal and project details. Then, the committee reviews the form and contacts an engineer for a home inspection and cost estimate. Together with the applicant, they complete a Loan Request Review Form gathering financial and household information. The committee periodically meets to approve loans, determining sizes based on their discretion. Disbursements occur in two installments, contingent on satisfactory completion of construction work. Repayment typically starts 30 days after the first tranche. Finally, an HFHE engineer inspects completed work for quality assurance. Loan documents are maintained by the partner NGO for audit, while CBOs keep records for active loans. Additionally, the average cost per loan includes engineer fees for initial visits and inspections.

With this simple scheme, HFHE provides finance resources to the communities and the poorest homeowners in Egypte. Thanks to it, and without the burden of the financial system, people can have an affordable and decent housing.