Makoko Neighborhood Hotspot

Main objectives of the project

The Makoko Neighborhood Hotspot, developed by FABULOUS URBAN from 2013 to 2017, is a vital infrastructure hub in Lagos' Makoko slum, providing essential services like biogas-linked community toilets, biogas production, water treatment, and farming pipes. Serving as both a business incubator and community empowerment center, it supports roughly 200 people and aims to inspire similar initiatives in other low-income areas. Managed by the Makoko Neighborhood Hotspot Multipurpose Cooperative Society Limited, the Hotspot exemplifies decentralized, low-cost interventions that address critical infrastructure needs while promoting sustainable development and community resilience.

Date

- 2017: Construction

Stakeholders

- Architect: FABULOUS URBAN

Location

Country/Region: Lagos, Nigeria

Description

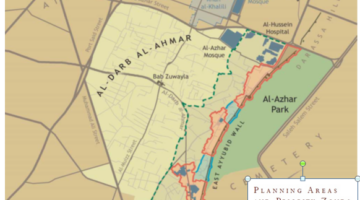

Housing is so much more than brick-and-mortar solutions. Above all, housing policies must provide infrastructure to a community. In the context of urban slum settlements, facilities like the Makoko Neighborhood Hotspot are of paramount importance, serving as a beacon of hope and innovation for communities often neglected by conventional urban development plans. Between 2013 and 2017, FABULOUS URBAN developed and implemented the Makoko Neighborhood Hotspot as part of the broader Makoko Urban Design Toolbox and the Makoko/Iwaya Waterfront Regeneration Plan. This initiative aimed to provide both technical and social infrastructure to one of Lagos' most well-known slum settlements, Makoko.

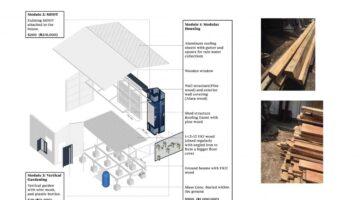

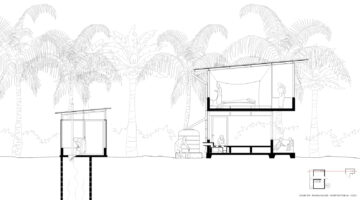

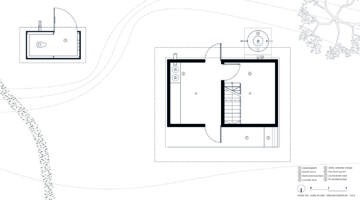

The Makoko Neighborhood Hotspot functions as an infrastructure hub, delivering essential urban services such as biogas-linked community toilets and serving as a business incubator promoting waste-to-energy principles. Moreover, it acts as a community empowerment tool and learning center, enhancing the social fabric and economic opportunities within the community. Despite the challenging decision-making processes faced by the underserved Makoko residents during the conceptualization and building phases, the Hotspot emerged as a carefully and ambitiously designed structure, symbolizing more than just an architectural feat.

In December 2015, following the completion and inauguration of the structure, the project entered its second phase, culminating in the formation of the “Makoko Neighborhood Hotspot Multipurpose Cooperative Society Limited” in 2016. Officially registered with the Lagos State Department of Cooperatives, this body now manages the operational and administrative functions of the Hotspot. With 20 members and a 7-strong management committee, the cooperative is responsible for hiring, payment, and supervision of employees, supported by three business plans designed to ensure sustainable operations.

By December 2017, the end of the third project phase, the Hotspot began providing critical infrastructure to approximately 200 people, including biogas-linked community toilets, biogas production, water treatment, and farming pipes. During the pilot phase, 10 families received cooking gas, refilled at the Hotspot with specially designed biogas rucksacks. As a business incubator, the Hotspot serves as a prototype for replication in other parts of the community and similar slum or low-income settlements in Lagos State.

Facilities like the Makoko Neighborhood Hotspot demonstrate a model for addressing the severe lack of infrastructure in many underserved communities. They embody decentralized, strategic, yet low-cost interventions that not only meet immediate needs but also inspire long-term solutions and governmental action. By empowering local residents and fostering sustainable development, such initiatives play a crucial role in transforming slum settlements into vibrant, self-sustaining communities.