Project Description

Since the hurricanes of September 2013, Cooperación Comunitaria has been working in the Montaña de Guerrero region in Mexico.

The Reconstruction of Habitat project was implemented first in the community of Obispo, in the Municipality of Malinaltepec, after assessing the magnitude of the problems caused by hurricanes and is designed to enable replication in other communities.

This comprehensive habitat reconstruction project has improved the living conditions and increased the resilience of the residents of Obispo by:

- reducing the risks of disaster through the development of a landslide risk map, which has resulted in the relocation of four houses;

- promotion of the sustainable management of natural resources through practical and theory-based workshops about reforestation to reduce landslides;

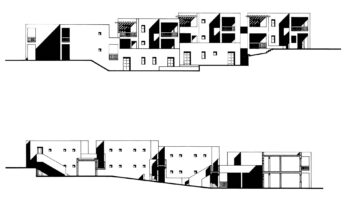

- a community centre which was built by the community and acted as a prototype

- a practical construction workshop for the subsequent self-build of 33 reinforced adobe houses and 31 energy-saving stoves;

- recovery of maize crops using agro-ecological[1] techniques.

The project started in September 2013 and finished in June 2015. It has now moved on to its second stage and is being replicated in three other communities of the Montaña region. It takes a comprehensive approach by tackling the multiple dimensions of vulnerability.

[1]The application of ecology to the design and management of sustainable agro-ecosystems.

Aims and Objectives

The main aim of the project is to reduce the vulnerability of the population in the region of Montaña de Guerrero by increasing the resilience of people living at risk and through the comprehensive reconstruction of their housing and habitat.

This is met by the following objectives:

- Reducing the risk of disasters, increasing resilience of residents through detailed risk analysis and mapping, increasing residents’ knowledge regarding their territory and the risks of disaster.

- Reinforcing housing for protection against earthquakes and winds through the architectural, structural and materials analysis of traditional adobe housing, and improving their suitability as living spaces by optimising temperature, acoustics and lighting.

- Recovering the community’s traditional knowledge of their territory, reinforced construction techniques with adobe and sustainable management of natural resources, respecting social and cultural norms in the region, preserving traditional productive spaces.

- Improving knowledge of agro-ecology techniques in order to limit the use of agro-chemicals, reduce plot rotation, avoid soil degradation, deforestation and therefore reduce the risk of landslides.

- Strengthening the organisational and decision-making capacity of the community. Strengthening solidarity among residents and recovering traditional systems for community work, such as “mano vuelta” (reciprocal community work).

- Improving the health of residents, reducing deforestation and the associated risk of landslides through the self-build of energy-saving stoves, which reduce the presence of smoke in the kitchen and the prevalence of lung and eye disease.

- Strengthening the community’s autonomy by using natural construction materials and reinforcing food self-sufficiency.

The region of Montaña de Guerrero is home to 85% of the indigenous population of the State of Mexico. This project:

- Directly benefitted 92 Me’phaa or Tlapanecos families whose housing and crops were affected by earthquakes, winds, heavy rain and landslides with: the construction (by the community itself) of a community centre/children’s library, and 33 houses with 31 energy-saving stoves.

- Indirectly benefitted 275 families with capacity-building workshops on the above mentioned skills (e.g. self-construction with reinforced adobe), as well as community development workshops and risk diagnosis.

Context

Eighty-one per cent of residents in the municipality of Malinaltepec live in poverty. They are in the most seismically active region of the country and in an area where winds can reach up to 120 km/h. Local people are highly vulnerable to and affected by these factors, as well as hurricanes and landslides with 70+% of residents reporting damage to their houses.

In September 2013, Hurricanes Manuel and Ingrid hit western Mexico, causing 200 deaths and affecting 230,000 people. In the region of Montaña del Guerrero, these phenomena caused numerous landslides, affected communication channels and infrastructure, led to the loss of crops and irreparable damage to over 5,000 adobe houses.

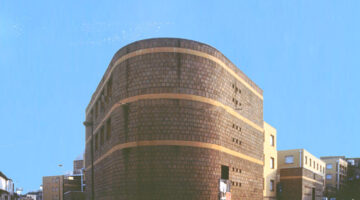

In addition to these conditions, migration has also been a factor in the loss of traditional knowledge, both in construction techniques and in the management of natural resources such as forests, which in turn has increased the vulnerability of residents. This loss of knowledge has led to gaps in the application of adobe construction techniques such as: lack of stone foundations and skirting boards in 86% of cases which causes dampness and deterioration of the walls; lack of an internal structure which debilitates the structure as a whole and weakens the corners; and inadequate anchorage from the roof to the walls which affects the resistance to strong winds, causing the roof to blow off.

Residents tend to attribute these damages to traditional use of adobe, when in reality they are due to technical omissions.

Key Features

Women from the community asked Cooperación Comunitaria to help with the reconstruction of their houses which were affected by hurricanes and so the organisation carried out a diagnosis of damage and the causes. When seeing the size of the problem caused by landslides, high deforestation and the impact on crops and houses, Cooperación Comunitaria brought together an inter-disciplinary team: a geologist, biologists, forestry and agricultural engineers in order to carry out an analysis of the risks and combine that information with the traditional knowledge of the community and a geological study of the territory.

The team of architects, an engineer and the community committed to working together to develop and implement a comprehensive project. Risks maps were developed and workshops were carried out to improve the skills and knowledge within the community, to identify how to relocate certain houses and areas for growing crops and to build new houses as well as improve residents’ resilience to future natural events.

The selection criteria for the beneficiaries were: permanent residence in the community, having suffered considerable damage to housing and crops, availability to participate in the community process and willingness to provide labour. Residents from affected neighbouring communities also participated in self-build workshops on using reinforced adobe. Decision making took place at community assemblies at which objectives were defined, internal systems and a project calendar created and committees set up to coordinate construction. Participants had control over each stage of the project. Their active participation in the workshops, which were delivered using participatory techniques, helped with the knowledge exchange between the community and Cooperación Comunitaria, and new techniques were incorporated through learning by doing. Community development officers were trained to supervise and monitor construction and they will act as the technical advisers in the next communities to be included in the programme.

A broad range of stakeholders took part in the workshops:

- Community authorities: in calling for assemblies and workshops; (Community authorities are a moral and legal entity in the indigenous law system. They have religious and political power in the communities and are recognised by the Mexican government and can sometimes act as representatives of the law).

- Local authority: providing communication about the activities and the reinforced adobe construction workshops to wider audiences and to other communities; (The local authority endorsed one of the workshops and brought together the community representatives from across all the municipal area).

- Community Goods Commission: involved in the sale of stone for foundations; (as there are no providers of materials within the involved communities, these materials were instead sourced from the ‘Office of Communal Goods’, which administers the natural resources of the municipality. This meant lower costs and benefits to the local economy).

- Metropolitan Autonomous University: undertaking tests on the community adobe bricks and land resistance.

- Guerrero Autonomous University: Diagnosis and landslide risk maps.

- Cosechando Natural (Natural Farming): advisor on agro-ecology techniques.

SAI Group: structural calculations and resistance simulation in housing for the development of a housing model with reinforced adobe.

What impact has it had?

Cooperación Comunitaria supports the needs of people from rural areas in order to exercise their right to housing. Currently, government bodies are reluctant to use local building materials, classifying these as precarious in the official regulation. Faced with this, the project aims to reclaim the benefits of these materials, proving that they are resistant, adapted to the local climate and culture, less expensive, less polluting and supportive of a better quality of life.

Cooperación Comunitaria is a member of the Mexican Social Production of Housing Network which seeks agreements with national institutions for improved housing. This network participates in the National Habitat Commission, seeking changes in the legislation to increase attention on the qualitative aspect of housing as currently these are purely focused on quantitative aspects.

How is it funded?

After the hurricanes, Cooperación Comunitaria coordinated a fundraising programme in Mexico City in collaboration with individuals and civil society partners. It was this emergency humanitarian fund which covered the initial costs and the initial participatory analysis work be completed. Subsequently, funding was secured from the Merced Foundation for disaster-risk reduction, recovery of maize fields, reforestation and capacity building activities.

The Mexican Federal Government, through the Social Development Institute, provided resources for the construction of the community centre/children’s library. The ‘Sharing with Guerrero’ Fund supported the self-build of 33 reinforced adobe houses and 31 energy-saving stoves.

There were MXN (Mexican Pesos) 2. 5 million (USD $140,000) received for materials, administrative costs, transport, training and learning materials. Cooperación Comunitaria provided another MXN 105,000 (USD $6,000) through donations and contributions from partners, and the support of national and foreign foundations (Misereor, Misión Central, Fundación Sertull y Fundación ADO) for the second phase of the project in three communities.

The community provided labour, produced adobe bricks and pajarcilla (a mixture of clay, water and hay or dry grass) to insulate the roofs, and food and accommodation for Cooperación Comunitaria’s field team. The community contributes both materials and a monetary contribution of MXN 1,000 (USD $55) to a communal loan facility. These savings enable people who cannot provide adobe bricks to access a loan of MXN 3,000 (USD $165) which is used for building materials and which is repayable in one year.

The total cost of a house (materials, labour, eco-technologies) is MXN 117,000 (USD $6,500); or MXN 140,000 (USD $7,700) if you include the costs of the activities (mapping, diagnostic, etc.). Cooperación Comunitaria is registered as a Contractor so is able to obtain government housing subsidies, which represent 58% of the costs (MXN 64,500 = USD $3,500), and the rest is covered by the beneficiaries’ contributions (MXN 1,000 = USD $55) and materials, plus contributions from donors for toilets and stoves.

Why is it innovative?

The main innovation is the methodology for comprehensive community work which reduces vulnerability and improves living conditions. Programmes for disaster-risk reduction and self-build housing have a long history in Mexico, but none of them combine an increase in community resilience, capacity building, sustainable management of natural resources, use of local materials in construction, community development and an economy based on solidarity. The combination of traditional indigenous knowledge as a risk reduction factor and new adaptations to well-established building techniques is another innovation. The participatory comprehensive methodology implemented by Cooperación Comunitaria through an interdisciplinary team ensures the appropriateness of the programme’s objectives and activities in relation to the needs of the communities. The project takes into consideration the community’s cultural, economic, environmental and climatic conditions. It puts forward traditional techniques and proven technology, which are adapted to local conditions, thus guaranteeing their acceptance. Participation in the project helps incorporate the effective use of solutions developed by the community themselves.

This type of innovation can, for example, be seen in the adaptation of traditional housing models. Some elements no longer in use have been integrated into the widespread adobe model such as:

- stone foundations and stem walls, with added reinforcement from adobe buttresses;

- concrete frames with fixings for the roof’s wooden frame;

- larger quantity of nails calculated according to the wind speed and the suction force applied to the roof;

- improvements in the size of adobe bricks;

- reductions in joints and horizontal elements for each three courses to improve seismic resistance;

- pajarcilla for insulation;

- earth floors to improve temperature control

- lime-based white paint;

- translucent panes to improve lighting.

What is the environmental impact?

The increase in knowledge of construction techniques using local materials and eco-technologies, reforestation and landslide risk analysis all contribute to greater awareness of and consideration for natural resources as well as increased community resilience.

Cooperación Comunitaria favours the measured use of local materials in construction, such as adobe, local wood and the organic insulation of roofs using pajarcilla. This avoids the need to transport concrete blocks and steel structures to the communities from the city of Tlapa de Comonfort, reducing CO2 emissions by 22% and preventing the emission of 482 kg of CO2 per house, which translates into a total saving of 16 tonnes for 33 houses. It is worth noting that by using local wood for roof structures, arches, doors and windows, the users of the housing projects expressly commit to planting 10 trees for each house constructed, promoting preservation of resources for future generations. The project includes self-build dry toilets (composting toilets) in each house, which prevents pollution and excessive water use, whilst at the same time protects and increases the quality of arable soil by avoiding the contamination caused by untreated human waste.

The resistance of the houses was measured through seismic and material resistance tests and increased using new elements such as buttresses, reinforced roofs and stone foundations. The main cause of landslides is deforestation. The use of agrochemicals depletes arable land, thus contributing to degradation of forests. The implementation of agro-ecological techniques reduces the contamination of soil and underground water through the reduction of agrochemical use. The increased skills in sustainable forest management, use of energy saving stoves and reductions in crop rotation through agro-ecology has reduced deforestation and the risks of landslides.

The use of open fires generates significant wood consumption, causing progressive clearance of the environment. According to the National Commission for Protected Natural Areas, a rural family cooking on open fires can consume up to 32 mid-sized trees each year. By using self-built energy-saving stoves, 40% of deforestation related to wood consumption has been reduced, preventing the emission of 200 tonnes of CO2 and the cutting of 775 trees each year, promoting the reduction of greenhouse gases. In addition, this comprehensive project includes community workshops on reforestation and awareness-raising.

Is it financially sustainable?

A comprehensive project, Reconstruction of Habitat does not depend on a single funding source. In 2016, it has not only managed to fundraise from a number of foundations but has also established alliances with two other organisations interested in the programme’s social aim: a German international cooperation agency, Misereor; and a Mexican foundation, Fundación Compartir. These alliances have enabled the continuation of the regional expansion of the project and mid- and long-term planning. Other foundations have offered their collaboration or have expressed their willingness to participate in the future under the same scheme, due to the achievements and impact achieved in the short-term. These include Fundación ADO providing funding of MXN 500,000 (USD $25,000) and Fundación Sertull, providing funding of MXN 360,000 (USD $20,000).

The programme requires beneficiaries to have previous savings and access to credit. However, Cooperación Comunitaria thinks that for the most vulnerable people, getting credit without savings puts them in an impossible situation. For this reason, following the operational regulations of CONAVI (National Housing Commission), people can contribute in-kind savings through the provision of adobe bricks, covering 5% of the construction costs. Families receive the support of Cooperación Comunitaria with in-kind savings, their contribution of manual labour and receive personal advice on how to manage their micro-credit. Habitat for Humanity, the authorised Contractor Body by CONAVI and project partner, serves as the financial actor in charge of verifying the savings contribution and providing micro-loans.

Cooperación Comunitaria is developing a system of savings and loans through community funds, which are administrated by the participants themselves. In this way, each family saves from the beginning of the project and when the time comes to contribute to the house, they have capital to act as collateral for the micro-credit. Cooperación Comunitaria has already implemented this model in Veracruz state in a separate programme and it worked well, although implementation takes time.

The use of local materials reduces costs and promotes self-sufficiency, reducing dependency on industrial materials.

A productive space for coffee processing in the house is planned for the second stage, as this is the residents’ main activity. A space will be allocated with a modular roof with mesh for coffee drying, whilst other productive activities can take place underneath the living spaces.

What is the social impact?

Participants were involved in communal work focused on collective collaboration to achieve common goals. Better communication, willingness and cooperation among residents was evident in construction, reforestation and their work on risk analysis, as well as in the commitment of each resident as part of a strengthened community. Likewise, the project organisers have noticed an increase in empathy among members, which has reduced problems and misunderstandings. Also, a greater sense of responsibility in decision-making through the organisation of the project activities was evident, as well as the development of working teams in construction and agricultural activities and when the community reached legal agreements via discussions in assemblies. An example of this is the increased participation of members in assemblies. At the beginning, only leaders would participate, but latterly members engaged in discussions, and Cooperacion Comunitaria became witness to a process driven by the communities – whose members engage in debates about fairness in beneficiary selection, community work, etc.

Working together also increases the organisational and decision-making capabilities of members of the community in the long term. In this way, it facilitates the independent design and development of future projects. The people who participated in the project have shown their ability to judge short-term programmes and their lack of sustainability; they are able to work independently and have a reduced dependency on handouts.

The area has many government programmes that are based on people receiving a monthly monetary sum, with the only requirement being that they attend meetings or events. This is seen as a way of receiving income but does not help people to become self-sufficient. On the contrary, they are dependent on this handout that can stop at any point. The government also runs programmes providing fertilisers and agrochemicals to farmers in the area without them knowing how to use them properly. This project, instead, is looking to promote independence and self-sufficiency, with people being able to produce their own housing and food. Participants increased their construction skills to produce reinforced adobe houses and energy-saving stoves. They have also gained knowledge of the causes of risks in their local area, their role in these events and the importance of the measured use of resources.

People who participated in the project are safer as their houses are resistant to the elements; significantly reducing their vulnerability towards landslides and natural phenomena such as hurricanes, strong winds and earthquakes. In this way, there is increased resilience towards the effects of climate change. The residents have the tools to identify risks in the long term. All community members have access to the risk map, which they can consult when necessary. A year after completion, the houses faced strong storms without any damage. The housing design respects the social and cultural norms of the region and preserves traditional productive spaces (for example for coffee production), and the project reduces the loss of traditional knowledge in construction techniques and resolves the technical issues that lead to damage such as cracks and humidity in walls. Self-build construction of new housing has helped to solve overcrowding situations through the building of new homes for young families. The project has an impact on living and health conditions: natural lighting was improved and thermal and acoustic insulation increased with mud tile floors and pajarcilla insulation in the roof; and the energy saving stoves help reduce the amount of smoke produced, helping to avoid respiratory problems as well.

Barriers

The main barrier faced was the effect of the federal government aid programmes, making people familiar with receiving resources without doing any work. Because of this, the organisation of the project, communication and participation were a challenge at the beginning. This was resolved through assemblies, talks and community development workshops where dialogue, decision-making and participation were promoted and facilitated.

Another obstacle was that prior to the construction of the housing, a road was widened through the whole community, which involved works that complicated construction logistics and made the attendance of some stakeholders at the assemblies difficult. Logistical arrangements were adjusted, the wood from felled trees was put to use once the road was open and the construction concluded before the rains as planned.

Lessons Learned

The main learning point for the project was being able to adjust the finance and work schedule in line with the activities of community members, taking into account agriculture cycles and cultural celebrations within the community. This helped Cooperacion Comunitaria better understand the community’s pace and way of working.

Another important point was knowing more about their culture, rituals, medicines and traditions, which helped them to adjust the project for the next communities in the same local authority area, with whom they are currently working.

Whilst finishing the Community Centre some modifications were made following residents’ comments, which allowed some structural modifications to be made with the engineer in order to facilitate the construction process. The programme is continuing to improve the techniques of lime-paint, floors, the ways of using pajarcilla for insulation, etc.

Evaluation

The impact of the project has been assessed by obtaining baseline indicators, through a community audit. The results were compared with those obtained at the intermediary and final phases of the project. Qualitative indicators were assessed with techniques such as ethnographic analysis and a community biography in the initial stage, which provided data on appropriate living spaces, cultural use of spaces and adaptability. Surveys and technical diagnoses were carried out, measuring damage, risks and gaps, which provided baseline indicators. Four follow-up visits have been carried out following the end of the project in 2015.

Recognition

- 2015 Razón de Ser (Raison d’être) Award, Sustainable Habitat category, presented by Merced Foundation and Kaluz Foundation.

- Semi-finalists for the 2016 Fuller Challenge, Buckminster Fuller Institute.

- Representative in the Mexico pavilion, 2016 Venice Architectural Biennale.

- Enlace Ciudadano (Citizen Link) programme in CDMX radio, presentation on projects and perspectives, July 2015.

- Project presentation in Ciudadana (Citizen) Radio, November 2015.

- Participation in HIC-AL publication “Transformative Experiences in Social Production of Habitat”.

- “Obispo residents: traditional knowledge incorporated to strengthen their resilience” Article published by UNISDR.

- Visitors have included HIC-AL/Franciscan Central Mission (Germany); MISEREOR (Germany); ADO Foundation (Mexico) and National Housing Commission – CONAVI (Mexico).

Transfer

This project is currently being replicated in three communities in the same local authority area (San Miguel, Laguna Seca and Moyotepec). Since October 2015, they have completed a socio-economic audit, risk analysis and mapping, as well as building a traditional medicine centre (which served as a practical example for the construction workshop).

Community workshops on risk reduction, community development and capacity building in construction of reinforced adobe housing have taken place. They will build 81 energy-saving stoves, 60 dry toilets and 110 reinforced houses, as well as three community garden centres with native species for reforestation. Capacity building activities will be carried out on resource management, cooperative development, self-build and eco-technology maintenance and six community development officers will be trained. In order to replicate the project, Cooperacion Comunitaria have acquired the certification needed to be able to transfer a federal subsidy from the National Housing Commission (CONAVI) to the residents, applying the constitutional right to housing for any Mexican citizen.

Through partnerships and presentations, 17 communities have come forward to ask to be involved in the development of similar projects, which are currently being considered. One of Cooperación Comunitaria’s programmes is focused on research into adapting living spaces to their context. In the case of Montaña de Guerrero, the project has already been implemented and tested and for this reason they plan to work with the same approach in the same region, in communities keen to work with them.

The methodology developed by Cooperación Comunitaria was designed to adapt to different geological, climatic, social and cultural contexts. Participation of the residents ensures the relevance of the activities in relation to the needs of each place, through the stages of needs analysis, architectural analysis of traditional housing, diagnostic and prevention of disaster risks, participatory housing design, capacity building, adapted housing and sustainable management of public resources. In that sense, the project is fully transferable to marginalised rural areas in Mexico and other countries that are exposed to disaster risks, even if the solutions developed are unique to each community.