The renter equity program, Cincinnati, OH

Main objectives of the project

Implemented in a neighborhood of Cincinnati, the renter equity program empowers renters to accumulate financial assets while actively engaging in and reaping the benefits of managing their apartment communities. Since its inception in 2000, the program has expanded from one to three apartment communities, with Cornerstone Renter Equity broadening its approach to include supporting families in enhancing financial literacy and attaining financial objectives. Residents emphasize that their contentment with the program primarily arises from the sense of community it cultivates, alongside the augmented wealth and financial stability it brings. For Renters Equity, having an affordable home is also enabling people to have financial stability thanks to their collaboration and involvement in the building.

Date

- 2000: Implementation

Stakeholders

- Cornerstone Renter Equity

Location

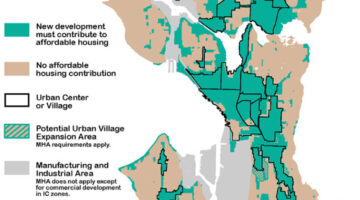

Country/Region: Cincinnati, United States of America

Description

The Renter Equity program was initiated in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood of Cincinnati, aiming to address the financial struggles faced by working-class individuals who are able to pay rent but find it challenging to afford other expenses. This program operates under the premise that renters lack house equity, despite making monthly payments towards their residence, thereby hindering their ability to access the value they've invested in the property for various purposes.

Cornerstone Renter Equity, established in 1986 as a community development loan fund, conceived the renter equity program to have a more significant social impact in Cincinnati. The program awards "equity credits" to residents upon completion of specified "renter obligations," which include timely rent payment, attendance at monthly tenant meetings, and participation in assigned apartment community upkeep tasks. These tasks typically require one to two hours per week and may involve property maintenance or contributing to property management decisions.

Residents can earn a maximum of $10,000 in equity credits over a ten-year period, which are held in a reserve fund managed by Cornerstone. These credits become vested after five years, at which point participants can withdraw them as cash or borrow against them for purposes such as education expenses or debt repayment. However, the program is tailored to a specific target audience: working-class individuals with limited financial assets who do not currently own or plan to purchase a home and hence lack a means of accumulating home equity.

The structure of the renter equity program revolves around three key components: the Renter Equity Agreement, Resident Association Agreement, and House Rules. These documents outline residents' obligations and the property management system's structure, emphasizing the earning of equity credits through fulfilling responsibilities. Prospective residents undergo a comprehensive orientation process, attending three monthly sessions to fully understand program requirements.

Residents benefit from community events and initiatives facilitated by the program, such as block parties, summer camps, monthly management meetings, and collaborative projects like building a playground together. Participants have reported experiencing greater financial security and satisfaction with their apartment communities as a result of accumulating equity credits. They have utilized these credits for various purposes, including funding long-term ventures and addressing financial needs such as paying for education or medical expenses.

While residents appreciate the opportunity for control over property management and the quality of their living environment, the primary appeal of the program, according to evaluations, lies in the sense of community fostered through participation. A majority of residents stay for five or more years and accumulate significant equity, though most end up using the funds to pay off debt or cover essential expenses rather than for investment or purchasing assets like cars or homes.