The Arroyo, Santa Monica

Main objectives of the project

Santa Monica's efforts to tackle its housing crisis and mitigate climate change converge in projects like the Arroyo. The city's commitment to affordable housing is evident in its mandate to create over a thousand new units annually, with a focus on affordability. The Arroyo exemplifies this mission, providing 64 units tailored to different income levels and incorporating sustainable design elements like photovoltaic cells and natural ventilation. Its recognition with prestigious awards like the 2020 LEED Homes award demonstrates its success in marrying affordability with environmental responsibility, serving as a model for future developments amidst California's dual challenges of housing and climate.

Date

- 2019: Construction

- 2020: Ganador

Stakeholders

- Promotor: Community Corp.

- Constructor: Benchmark Contractors

- Architect: Koning Eizenberg Architecture

- John Labib + Associates

Location

Country/Region: Los Angeles, United States of America

Description

The affordable housing crisis in Santa Monica mirrors that of California as a whole, with over half of households spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent. The city also faces the daunting task of meeting the goals set in the 2021 regional housing needs allocation (RHNA): planning for an average of 1,109 new housing units annually for the next 8 years, with over two-thirds of them designated as affordable. This year's allocation represents a substantial increase compared to the previous RHNA cycle. To tackle this challenge, Santa Monica has implemented aggressive measures, including inclusionary housing (IH) regulations, to encourage the development of affordable housing units. Simultaneously, the city grapples with the climate crisis, experiencing higher average temperatures and prolonged droughts. In response, Santa Monica devised its 2019 Climate Action and Adaptation Plan, incorporating strategies to achieve carbon neutrality in buildings. Recent housing projects in the city, such as the 64-unit Arroyo developed by the Community Corporation of Santa Monica, epitomize this dual focus on sustainability and affordability.

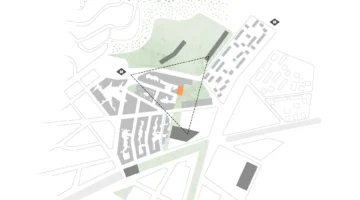

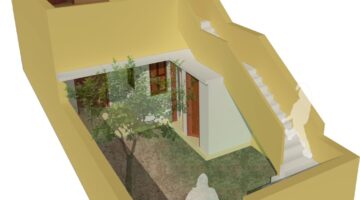

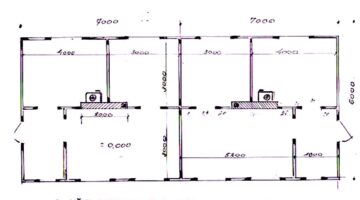

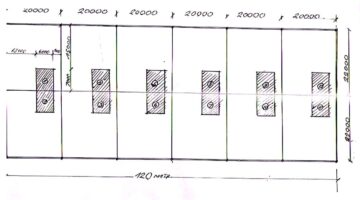

The Arroyo, a five-story building featuring two parallel wings connected by bridges on each floor, boasts a central courtyard that follows the path of the former arroyo, now replaced by a stormwater drain. This courtyard extends into a basketball half-court and picnic area with covered activity space. Additionally, indoor spaces cater to residents' needs, providing a vibrant community atmosphere. Two community rooms host various free programs, including fitness classes, financial management courses, and computer training sessions. Tailored programs for younger residents, such as afterschool homework assistance and college readiness courses, further enrich the community experience.

The genesis of the Arroyo lies in the city's housing and planning regulations applied to 500 Broadway, a downtown development proposed by DK Broadway in 2013. Subject to city requirements mandating affordable units or contributions towards affordable housing elsewhere, DK Broadway opted to provide a site for affordable housing a few blocks away, subsequently transferred to the Community Corporation. The financial backing, including low-income housing tax credits and loans from Bank of America, facilitated the Arroyo's development without city or state funding.

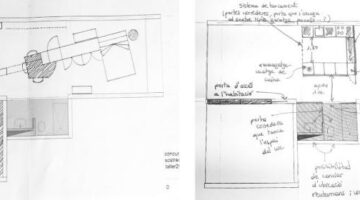

Sustainable design features are integral to the Arroyo's ethos. Natural airflow facilitated by the courtyard, bridges, and open-air corridors promotes ventilation and cooling without increasing energy demand. Photovoltaic cells and solar water heating panels harness Southern California's abundant sunshine, while high-albedo roofs and window shades mitigate excessive sun exposure. Proximity to amenities and a Metro light rail station encourages car-free living, supported by onsite bicycle parking and electric vehicle chargers. These sustainable elements, coupled with affordability, earned the Arroyo recognition, including a 2020 LEED Homes award from the U.S. Green Building Council.

The Arroyo's accolades extend beyond sustainability, with awards such as the AIA National Housing Award (2021) and the Jorn Utzon Award (2020) underscoring its architectural and societal significance.