LIFE REUSING POSIDONIA/ 14 social dwellings in Sant Ferran, Formentera

Main objectives of the project

Life Reusing Posidonia is a Climate Change Adaptation Project funded by the European LIFE + program. It integrates Heritage, Architecture, and Climate Change to explore sustainable solutions using local resources. The project focuses on reusing Posidonia, a type of seaweed, as a key material throughout the building.

Date

- 2017: Construction

Stakeholders

- Architect: Joaquín Torrebella Nadal

- Architect: Alberto Rubido Piñón

- Promotor: Institut Balear de l’Habitatge (IBAVI)

Location

City: Formentera

Country/Region:

Description

Life Reusing Posidonia is a Climate Change Adaptation Project financed by the European LIFE + program for nature conservation projects. The project links Heritage, Architecture and Climate Change with the aim to recover the local resources as a cultural approach in the contemporary research for sustainable solutions.

Traditional architecture has been a constant reference, not for its forms, but as a way of working. By doing so, we look for the available local resources: the juniper trees are now fortunately protected and the sandstone quarries (marès) have been depleted. Therefore, we only have what arrives by sea: Posidonia. So we propose a shift in approach which has been applied to every single part of the building:

“Instead of investing in a chemical plant located 1,500 km away, we could invest the same amount in local labor, who should lay out the Posidonia to dry under the sun and compact it by hand. Sea salt acts as natural biocide and is completely environmentally friendly.” The use of dry Posidonia as thermal insulation reminds us that we do not live in a house but an ecosystem.

1. TO DEMONSTRATE:

The viability of constructing the prototype with an additional cost of 5% over the usual price of the IBAVI social housing buildings.

2. TO REDUCE:

63% of CO2 emissions during the construction of the building.

775,354.6 kg/CO2 have been saved. Calculation performed through the TCQ program of ITEC.

75% of useful energy during the lifetime of the building.

Nearly Zero Energy Building (nZEB), with maximum consumption of 15 kWh/m²/year (17,226.30 kWh/year).

The average thermal comfort measured in situ is 21ºC in winter and 26ºC in summer.

60% water consumption.

Maximum limit 88 l/person and day. Average consumption based on the tenants’ bills.

50% waste production during the construction phase

36.98 tones have been saved due to in-site reusing measures.

3. ORGANIZATION & PROGRAM

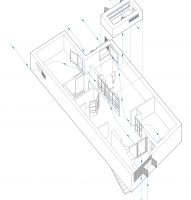

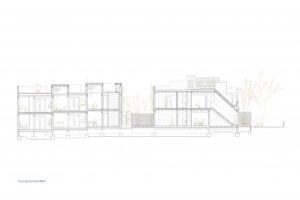

The two street facades facing main sea breezes (North & East) to cool in summer allow dividing the volume into two separate blocks with different orientations.

The entrance to all homes is directly on to the street.

All the dwellings face two directions and cross ventilation thanks to the layout of the living room in a Z shape and a bedroom at each corner.

All the materials have been selected through a market study based on their embodied energy and the transport cost to Formentera.

We tested solutions based on the recovery of eco-friendly local artisan industries with KM 0 raw materials, which are in danger of extinction. Usually these are small family companies that do not have eco-labels, but they can easily be inspected in person. The combined use of these available local materials with those imported that do have environmental labels is a replicable model that makes it possible to reduce more than 60% of CO2 emissions during the works. For instance, load-bearing walls with non-reinforced lime foundations, laminated wood slabs, white lime plaster on facades, sandstone cistern vaults, handmade glazed tiles, bricks baked in biomass mortar kilns, etc.

All indoor carpentry and the shutters on the ground floor were made of reused second hand doors and wood from the ‘Deixalles’ waste-management plant in Mallorca.

The organization of spaces and formal decisions have been the result of knowing the advantages and limitations of natural materials, which are more fragile. This fragility has become a design opportunity.