Woof & Skelle, Bremen

Main objectives of the project

The Woof and Skelle buildings in Bremen's Ellener Hof district, developed by Bremer Heimstiftung, form a new village-like neighborhood with 500 mostly subsidized apartments, focusing on timber construction for sustainability. The ensemble includes a five-storey building with a kindergarten on the lower floors and accessible flats above, and a two-storey building with additional kindergarten areas, an early intervention centre, and a parents' café. The design emphasizes renewable materials, with a high proportion of timber for flexibility and resource efficiency, incorporating low-tech climate concepts and strategic fire protection measures.

Date

- 2024: Ganador

- 2022: Construction

Stakeholders

- Architect: ZRS

Location

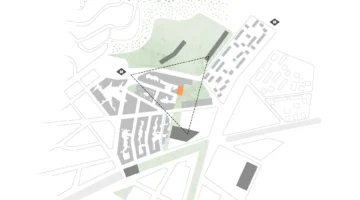

Country/Region: Bremen, Germany

Description

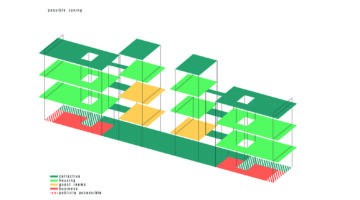

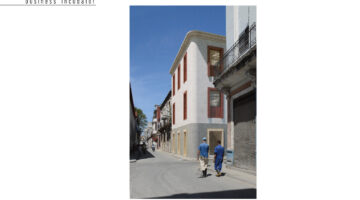

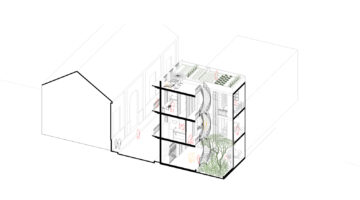

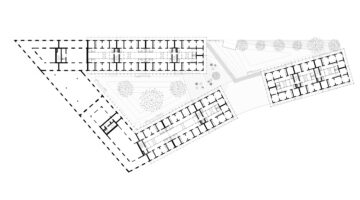

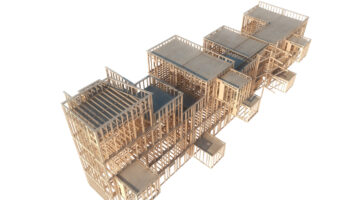

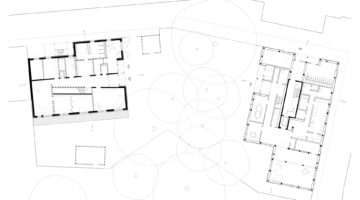

The two new buildings, Woof and Skelle, are part of the Ellener Hof district developed by the Bremer Heimstiftung. This new neighborhood in the eastern part of Bremen consists of 500 mostly publicly subsidized apartments and is designed to resemble a gradually grown village, largely constructed using timber. The building ensemble includes 9 flats and a kindergarten. In the five-storey building, the lower two floors are used by the kindergarten, while the upper three floors house 7 partially accessible and 2 fully wheelchair-accessible flats. The two-storey building accommodates additional kindergarten areas, an early intervention centre, and a parents' café. The wooden façade connects the buildings, forming a cohesive ensemble. The project is characterized by renewable building materials and a high proportion of timber construction: a skeleton construction allows for a high degree of flexibility in the event of conversion. In addition to the supporting structure and the exterior walls, the partition walls, the staircase, the lift shaft, and the balconies are also made of wood. A low-tech climate concept supports this circulation-friendly and resource-saving construction method.

By not sheathing the load-bearing construction and dimensioning the load-bearing wooden elements for burn-off, the fire protection concept allows visible wooden surfaces in all rooms. Even in the necessary stairwells, the construction of visible timber surfaces is made possible by compensations. Vertically projecting solid timber slats and horizontally cantilevering steel sheets limit the spread of fire across the façade surface, making the timber façade feasible. Both houses, the flats, and the kindergarten are designed for a low-tech climate concept—the desired values are largely achieved through the specific qualities of the building envelope. Diffusion-open, moisture-regulating surfaces allow for the elimination of expensive and high-maintenance technology. In addition to natural ventilation via the windows, the houses are equipped with a demand-controlled exhaust air system in the interior bathrooms.

The core idea of a circular, resource-saving building is reflected on several levels: the robust timber frame construction allows for a high degree of flexibility for conversions and a long service life. Attention was given to reversible connections and robust construction in the building elements. The building envelope and shell are deconstructible down to the level of the elements and building materials. The proportion of concrete was reduced to a minimum, and the timber structure is optimized for slender profiles. In addition to the supporting structure and exterior walls, the partition walls, staircase and lift shaft, the fire wall, and the balconies are also made of timber. The ceilings are partly constructed as cross-laminated timber ceilings and partly as timber-concrete composite ceilings. Where possible, the wooden components are left visible, characterizing the interior with their light-colored surfaces. The proportion of petroleum-based insulation materials has been reduced to the absolute minimum—cellulose, wood fibre insulation, and foam glass are used instead. The high proportion of wood (over 60%) makes the project a CO2 reservoir.