Continuity of an integrated planning approach over the last 30 years has led to the development of Freiburg as a leading exemplar of sustainable living in a compact car-lite city. Two urban extensions – Vauban and Rieselfeld – provide homes for 17,500 people and have been developed using low carbon technologies, self-build, and with excellent mass transit systems. The intention was to develop these districts to high environmental standards as well as ensuring that they had strong social structures and communities. A key success factor in Freiburg’s approach has been its focus on citizen participation and active democracy, enabling it to engage a wide range of stakeholders in its radical urban planning approach.

Project Description

Aims and Objectives

To create an environmentally and socially sustainable city through enlightened planning and pioneering use of renewable energy systems.

Context

Freiburg is an ancient university city with a population of 220,000 located in southern Germany near the Swiss and French borders. It is a rich city with a GDP per capita 11 per cent above the European average and has the highest concentration of sunshine in Germany, with more than 1,700 hours per year. Urban planning and development have always had a special impact on Freiburg. After the devastating destructions of the World War II and with 85 per cent of the inner city destroyed, the programmatic corner stones for Freiburg’s exemplary spatial and settlement development were laid out during the post-war years. The city was rebuilt from the 1950s onwards, taking note of traditional urban patterns and cultural heritage, but with a focus on sustainable development. In the 1960s, the crucial decision was made to hold on to the tram network as the backbone of urban development in Freiburg and consequently, to expand it accordingly. In addition to this, the “five fingers” concept was developed for the distribution of green spaces to clearly separate open zone from building zones. These elements – the tram as well as the division into green areas and building areas – are still the guiding aspects for Freiburg’s urban development today.

The Planning Department has long been a key department in the municipality and has always been progressive, introducing pedestrianisation, for example, in the city centre in 1949, and refusing to build shopping malls outside of the city. There is a stable political system, with the Green Party having dominance for the last decade. With up to 35 per cent of the overall city vote, the Green Party is the strongest in any major German city.

Key features

The process of sustainable city planning started in the 1970s when the citizens of Freiburg did not want to accept a planned nuclear power station. In 1986, with the nuclear catastrophe at Chernobyl fresh in their minds, Freiburg’s municipal council decided to have a future-oriented energy policy based on renewable resources wherever possible. This led to the development of Freiburg as a global first-rank model of sustainable urban life. It is a compact city development with car-lite systems.

Freiburg has a strong orientation to walking, bicycling, and public transport, with car-free areas and high levels of accessibility for people of all ages. It seeks to be ‘a city of short distances’. This involves three major strategies: restricting the use of cars in the city, providing effective transport alternatives to the car and regulating land-use to prevent sprawl. Two-thirds of Freiburg’s land area is devoted to green uses. Just 32 per cent is used for urban development, including all transportation. Forests take up 42 per cent, while 27 per cent of land is used for agriculture, recreation, water protection, etc.

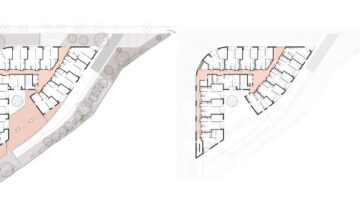

As a result of the Chernobyl catastrophe in 1986, Freiburg made the saving of resources the most vital factor for all future planning which included the clear prioritisation of public transport over individual traffic and goals to reduce energy consumption of buildings and realise future planning areas through self-financing schemes. The two major urban extensions Vauban and Rieselfeld were developed under these guidelines. Both developments have been built on brownfield sites – Vauban was on the site of a former military barracks and Rieselfeld on a sewage farm. Vauban is a neighbourhood of 5,500 inhabitants, located four km south of Freiburg town centre and is estimated to be one of the largest solar districts in Europe. All houses in Vauban are built to a low-energy consumption standard – maximum 65 kWh/m2/year (the average energy standard for new-build German houses is about 100 kWh/m2/year, 200 kWh/m2/year for older houses). Low-carbon technologies include heating from a combined heat and power station, solar collectors and photovoltaics. Self-build is used extensively in Rieselfeld, an urban extension for 12,500 people started in 1992. Direct mass transit links were created to the city centre. The current land-use plan for the city focuses on developing within the current city limits to optimise the existing infrastructure. Although the new concentration is on interior development, Freiburg’s population figures are still climbing and the number of jobs (mainly in the field of universities and of high-ranking scientific facilities) is also constantly increasing.

Freiburg’s success owes much to its democratic strength. Three key factors are direct citizen participation, dynamic planning, and consensus. Active democracy was the first step when citizens worked to oppose the planned nuclear power plant. This early activism has evolved so that citizens are directly involved in land-use planning, the city budget, technical expertise committees, developing public information on sustainability, and as shareholders in local renewable energy providers (e.g. solar, wind). The broad base of involved citizens is credited for Freiburg’s development of a consensus on sustainable development across the major stakeholders. This has enabled goals to be pursued steadily over decades.

Covering costs

The usual sources of income available to the city authorities have been used to deliver this work. The Vauban and Rieselfeld developments were built without any contribution from the city budget. The income received from selling the serviced plots of land to co-operatives, individuals and small builders covered the costs of the land and all the necessary physical and social infrastructure that the city provided.

Impact

- The standard of living in Freiburg is recognised as one of the highest in Germany, not only due to the natural climate and landscape advantages, but also to the active engagement of the citizens in decision making and sustainable city living.

- The citizens of Freiburg have a well-developed understanding of environmental issues, which affects their lifestyle choices.

- As a national exemplar of sustainable urban planning, ideas developed here have been used in countries around the world.

- The project itself involves the development of local government planning policies, which have also been used in other cities. Freiburg is very well known throughout Germany for its sustainable approaches, which have influenced both regional and national governments. Germany now has some of the strongest environmental protection policies in Europe.

Why is it innovative?

- Development of an integrated planning approach to develop an environmentally sustainable pattern of city living thirty years ago, before such approaches were widely recognised.

- Encouragement of citizen engagement in the decision making for the city.

- Recognition of the importance of an integrated mass transit system throughout the city in creating a ‘city of short distances’, enabling high levels of public transport use, cycling and walking.

What is the environmental impact?

Low-energy building is obligatory in the Vauban district; zero-energy and energy-plus building and the application of solar technology are standard. There are over 50 passive houses and at least 100 units with ‘plus energy’, which is estimated to be one of the largest ‘solar districts’ in Europe.

Freiburg is a centre for innovative sustainable energy generation – solar, wind, hydropower, co-generation and district energy. Extensive use of permeable ground surfaces, bio-swales (vegetated areas designed to attenuate and treat rainwater runoff) and green roofs helps save water. Property owners are charged a storm water fee according to the percentage of their land that is permeable.

The Freiburg Climate Protection Strategy 2030 provides a clear focus and wide-ranging framework for local action in key areas identified for effective GHG emissions reduction. The city’s focus is now on achieving the new target – a 40 per cent reduction by 2030 on the baseline year of 1992 – with the support of an action plan, a structure established to support the implementation process and engaging its citizens.

Vauban is virtually car-free with over 70 per cent of households not owning a car. Car owners have to purchase a parking space in a multi-storey car park on the outskirts of Vauban for US$23,350, plus a monthly service charge. Transportation planners make use of five mechanisms to encourage healthy and sustainable transportation modes – extension of the public transportation network; traffic restraint; channelling individual motorised vehicle traffic; parking space management; and promotion of cycling. Today there are 30km of tramway network, which is connected to 168km of city bus routes as well as to the regional railway system. Seventy per cent of the population lives within 500m of a tram stop.

Is it financially sustainable?

The stable political system, with a strong Green Party, is likely to ensure the continuity of funding sustainability in the city. The city takes a hard-headed commercial approach to development. Loans have to be repaid, grants are limited and only five per cent of the housing in Rieselfeld is funded by the municipality. Expenditure on roads is minimised, most of the streets are only four metres wide and limited to car use only. There is a betterment levy, with the city authorities taking one third of the increase in value on the sale of open land. Land for building is sold off in small plots (190 to 210m2) with limits on the number of plots any one group can buy, thus favouring small builders and co-operative groups. In Vauban, less than 30 per cent of the land area was built up by large developers, 70 per cent of the plots were sold to small builders and co-operatives, resulting in 175 different building projects.

Homes are reasonably affordable in the city, reflecting partly the German housing market with its low rate of house-price inflation. There is a high proportion of affordable rental housing (80 per cent of stock). Co-operative building groups help to keep home ownership affordable with building costs much lower than buildings with similar quality bought ready from a development company.

The city is one of the wealthier cities in Germany and it has created a specialised service sector relating to renewable technologies. The university is a leading institution for renewable energy research, with many manufacturing off-shoots. A variety of small eco-focussed businesses and eco-tourism have emerged. For example, Genova, a private enterprise building co-operative is pursuing ecological concepts of solar installations for publicly co-financed housing.

What is the social impact?

Freiburg has long had an emphasis on citizen engagement. There are many opportunities for citizens to be engaged within their communities and in city-wide campaigns for environmental improvement. When the two new urban areas were developed local community forums were established which acted as joint place promoters, offering critical support to the city council and through its energy and activism, encouraging it to move forwards.

Freiburg has long had an emphasis on citizen engagement. There are many opportunities for citizens to be engaged within their communities and in city-wide campaigns for environmental improvement. When the two new urban areas were developed local community forums were established which acted as joint place promoters, offering critical support to the city council and through its energy and activism, encouraging it to move forwards.

The new urban extensions in the city have a family friendly character, with the city’s emphasis on being a ‘city of short distances’. There are flourishing community centres where people can hold meetings, organise entertainment, have a meal etc. Community participation in the city’s Land Use Plan involved 19 working groups of technical officers and local communities.

In Vauban, the city used the principles of the community architecture movement, encouraging groups working together with their own architect to develop a block of buildings around a defined open space. In Rieselfeld there was a strong emphasis on self-build and the municipality provided serviced sites, enabling people to have homes costing up to 25 per cent less. Over 100 different builders were involved (20 per cent were co-operatives). Co-operative self-build improves the skills of those involved in a wide range of areas. Wide-scale development of eco-based industries has developed specialist skills in academia, services and manufacturing.

Emphasis on cycling and walking rather than car use, the availability of local produce and the development of close community networks all serve to improve the health and safety of local people. The car-lite living patterns, especially in Vauban and Rieselfeld, enable children to play safely outside of the home. The emphasis on social sustainability in all aspects of life has ensured a reduction in social inequalities. The housing development process has led to a wide range of designs and development and it is difficult to gauge people’s wealth from the outside of their house.

In 2008 the city of Freiburg used meetings as well as online discussions about participatory budgeting with the use of a budget simulator, enabling citizens to better assess the impacts of their choices. The results of this deliberative process were then collaboratively aggregated and edited by the participants of the process themselves.

Barriers

Initial resistance came in the early days from many of the city’s population, especially those who lived in the suburbs, who did not want to reduce their dependency on the car and wished to have out-of-town shopping facilities. There was also strong resistance coming from the developers who wished to have a free hand in the development of the city. Both were overcome by having a clear strategy for the development of the city and making this clear to developers and by convincing and inspiring the people that this was a good choice for the city through engagement in the discussion and decision-making process.

Lessons Learned

- Implement controversial policies in stages, choosing projects that everyone agrees on first.

- Keep plans flexible and adaptable over time to allow for changing conditions.

- Policies should include both sticks and carrots to encourage people to change behaviour, i.e. making parking more expensive and difficult, but making public transport, cycling and walking much easier.

- Organise land use and transportation on an integrated basis to ensure that travel distances can be kept short.

- Involving the citizens should be an integral part of policy development and implementation.

- Support from regional and national government is vital in helping local policies to work.

- Long-term goals need to be pursued on a consistent basis.

- City leaders have to be committed to long-term engagement, but always with the support and engagement of the people.

- Be creative and tactical in working with a wide range of different investors and other actors.

- Be proud of the achievements and celebrate them with the citizens.

- Continuity is vital.

Evaluation

Active monitoring is carried out across a range of city activities to ensure that the Freiburg Climate Protection Strategy 2030 is on target to achieve the planned GHG emission reductions of 40 per cent by 2030 on the baseline year of 1992.

Transfer

Freiburg has long been an exemplar par excellence for urban planners wishing to look for models of sustainable urban development. There is widespread media coverage of the pioneering work being done in Freiburg, as well as citation in academic literature. The city and its planning system have received many plaudits and awards over the last 30 years. Some more recent ones include the European City of the Year 2010 (Academy of Urbanism), the European Green Capital (Finalist 2009) and the Federal Capital for Climate Protection 2010.

The city has established the Freiburg Charter with a set of 12 principles to guide planning and development if a sustainable city is to be achieved. This is being widely discussed and used by planning authorities around the world, with many presentations and international congresses on the approach, as well as academic and professional visitors coming to learn directly how to establish a similar charter in their own situations and learn from its numerous good practice examples, including energy, transport, buildings and waste management.

Local towns and cities have adopted many of the examples set by Freiburg. Other German cities continue to learn from the experience at Freiburg, with both the planning professionals as well as city leaders seeking to develop similar approaches. The Freiburg model has spread to cities in neighbouring countries, including Mulhouse in France and Basel in Switzerland, as well as further afield. Freiburg is twinned with nine cities around the world and it continues to have close connections with them, providing support and planning guidance.

Freiburg has long had an emphasis on citizen engagement. There are many opportunities for citizens to be engaged within their communities and in city-wide campaigns for environmental improvement. When the two new urban areas were developed local community forums were established which acted as joint place promoters, offering critical support to the city council and through its energy and activism, encouraging it to move forwards.

Freiburg has long had an emphasis on citizen engagement. There are many opportunities for citizens to be engaged within their communities and in city-wide campaigns for environmental improvement. When the two new urban areas were developed local community forums were established which acted as joint place promoters, offering critical support to the city council and through its energy and activism, encouraging it to move forwards.