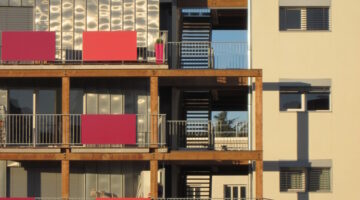

Village Vertical, Villeurbanne, France

Main objectives of the project

Initiated in the fall of 2005, the Village Vertical became a reality in June 2013 when 14 households, members of our variable capital cooperative established in December 2010, moved in. These households, from diverse backgrounds, collaborated to bring the project to fruition.Each household resides in an eco-friendly building they helped design, sharing certain spaces and resources to foster genuine neighborhood solidarity. This human-scale project integrates conviviality, responsibility, savings, mutual aid, ecology, and democracy. As the collective sole owner of the building, each household rents its unit within a democratic management framework that prohibits speculation and profit.

Date

- 2013: Construction

- 2005: En proceso

Stakeholders

- Promotor: Village Vertical Coop.

- Promotor: HLM Rhône Saône Habitat

- Architect: Détry-Lévy

- Architect: Arbor&Sens

- AILOJ

- Habicoop

Location

Description

The project began in 2005 when a group of four individuals sought to address their housing issues by designing a residents' cooperative. Only one couple from the original group remained until the project's completion, with others joining along the way. Initially, they attempted to acquire and convert existing buildings, such as an old factory, but abandoned this plan due to the volatile real estate market. To become more organized, they formed an association and dedicated several hours weekly to project development, including regular and thematic meetings focused on architecture, financing, and legal matters. In 2006, Habicoop approached the association, asking them to lead the cooperative housing movement in France. This partnership helped them secure a collaboration with HLM Rhône Saône Habitat, which enabled them to obtain land with support from Greater Lyon and Villeurbanne. By 2008, the land was secured, and discussions with architects Arbor&Sens and Détry-Lévy began. To ensure financial feasibility, two-thirds of the housing was allocated for home ownership, and one-third was designated for the "village." The building permit was obtained in 2010, and the association of future residents transformed into a cooperative. Habicoop devised a legal framework to compensate for the lack of formal recognition of residents' cooperatives, which was only established by the Alur law in 2014. From the start of construction in 2011 to the building's completion in 2013, residents ensured adherence to ecological standards. The artisans and architects, accustomed to traditional roles, were encouraged to adapt their approaches to the collaborative environment. Other partners, like AILOJ, which supports young people in integration, also joined the project.

Numerous contributors made the cooperative possible. Habicoop provided project management assistance, as well as legal and financial support. Architects Arbor&Sens and Détry-Lévy co-designed the project with residents. HLM Rhône Saône Habitat handled construction and financial backing. AILOJ managed the social housing units for young people in integration. Villeurbanne and Greater Lyon sold the land, with the Region granting a subsidy of 4,000 euros per unit. The Vertical Village is part of the social and solidarity economy movement, partnering with Enercoop for renewable energy, Miecyclette for organic bread delivery, Arbralégumes for organic produce, and Prairial for grocery deliveries.

Since there was no legal status for housing cooperatives in France before 2014, the Village Vertical operates as a "cooperative company with simplified shares and variable capital" with an initial capital of €380K. Residents collectively own the building and rent their units from the cooperative. Once the loan is repaid, an annuity can be distributed to them and their heirs. The social housing within the building is managed by HLM but will revert to the Village after 20 years.

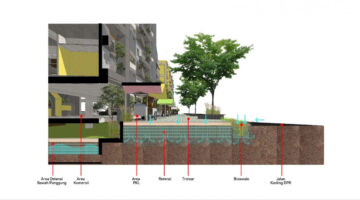

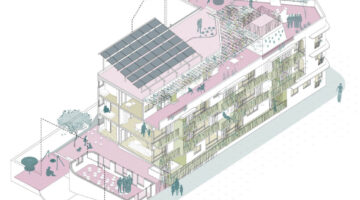

The building houses 34 units, 14 of which belong to the Village Vertical: two T1s for young people in integration, five T2s, two T3s, two T4s, and three T5s. Shared amenities include a laundry room, a common room with a kitchen, and a vegetable garden. The building is energy-efficient with wooden facades, a photovoltaic roof, and a wood-fired boiler. Generous common areas support the sharing of equipment and services, fostering community interaction and cooperation.

Each resident, cooperator or not, signs the Village charter, emphasizing cooperation, ecology, democracy, and a balance between individual and collective spaces. Collective ownership and decision-making are governed by a democratic process, with "one person, one vote" principle. Weekly "Vertical Thursdays" include a meeting and a shared meal for discussing issues and organizing tasks, while monthly mandatory meetings ensure task distribution. About sixty tasks are identified and assigned among residents, with larger roles shared by multiple people. Residents share household appliances and vehicles and organize group food deliveries in partnership with local cooperatives. Departing residents must resell their shares without profit, and new members are co-opted unanimously from a waiting list.

Since 2013, the "vertical villagers" have lived together according to their ecological and supportive ideals. Significant resident involvement was crucial in the building's design. Managing the cooperative demands balancing personal, professional, and community responsibilities. Young people in integration, though less involved, benefit from supportive neighbors. The village functions as a laboratory for sustainable living, sharing equipment, managing waste, cultivating a vegetable garden, and utilizing rainwater. Democratic discussions and decisions are a daily norm. Over time, outreach projects like community composting, shared gardens, and food deliveries have developed, and a Citiz car-sharing station has been established in the neighborhood thanks to the villagers' efforts.

The cooperative is non-profit, preventing real estate speculation and enabling access to property for those with limited means. It is part of the participatory housing movement, giving residents a say in their housing's design and management. Sharing spaces fosters solidarity and reciprocity within the community.

The project's success relied heavily on the support of partners like Habicoop and Rhône Saône Habitat, and the residents' determination was crucial for maintaining its ecological focus. Effective communication and mutual understanding among the various contributors were essential. Learning to co-manage the project was vital for both residents and professionals. Ultimately, establishing democratic processes and balancing collective and private life have ensured the cooperative's ongoing viability and functionality.