In January 2010, a devastating earthquake shook the Caribbean nation of Haiti to its core. The disaster and subsequent aftershocks killed an estimated 250,000 people, injuring 300,000 and displacing 1.5 million people, whose homes collapsed. Much of the country’s infrastructure was also destroyed as the magnitude-7 tremor reduced schools, hospitals, government buildings and roads to rubble. The country was left in crisis, its people living in makeshift accommodation, vulnerable to food shortages, poverty and rapidly spreading disease.

International humanitarian organisations responded en masse to help with the enormous relief effort. CRAterre – an organisation leading international research, training and action in the field of earthen architecture – already had a presence in the country and was asked to provide technical assistance to multiple local and international organisations involved in the post-disaster response and rebuild.

Rethinking construction

Prior to the earthquake, no building codes were enforced in Haiti. Many of the country’s structures were poorly built and simply disintegrated when disaster struck, leaving a massive death toll in their wake. The fragmented response efforts of numerous aid agencies and difficult terrain meant the rebuild process was particularly challenging.

Against this backdrop, CRAterre recognised the need for an alternative approach to the standardised industrial building techniques usually employed by international aid agencies involved in post-disaster response. Rebuilds are typically a very top-down process, where big aid organisations come in and build houses with a standard approach, all too often ignoring local traditions and techniques, and creating a secondary ‘aid’ economy, which excludes local workers.

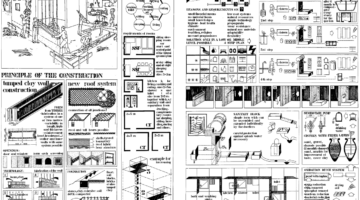

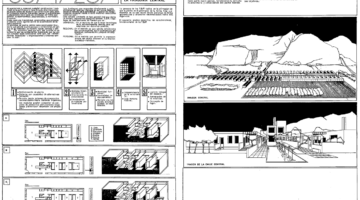

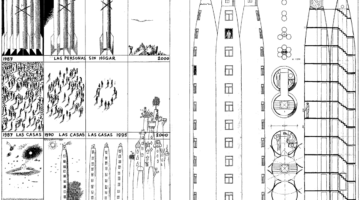

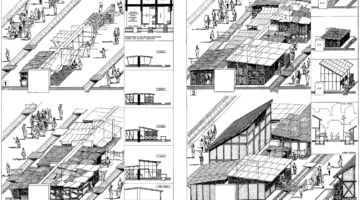

CRAterre used its research to promote a more unified approach that took into account the hugely varying physical, social, environmental, economic, cultural and governance factors across the country. It believed that by promoting improved local building techniques – known as Techniques de Construction Locales Améliorées, or TCLA – the country could become more resilient to natural disasters and improve its response when they occurred. The organisation was directly involved with 25 contracts for technical assistance and training and was asked to collaborate on numerous other projects, giving it scope to influence a wide range of organisations.

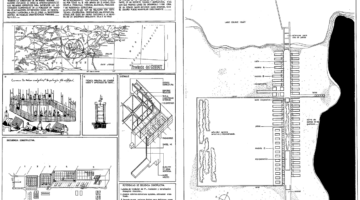

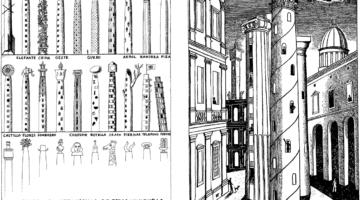

CRAterre’s focus was mainly on rural areas across Haiti, where resources and needs differ greatly according to the availability of materials, transport, facilities and climate. The hugely varied geography of Haiti also affects the approach to building foundations and the supply of water and sanitation. CRAterre’s team of experts began by evaluating traditional local building techniques, which vary widely, then refined them using the findings of their scientific research and local observations. Haitian builders were therefore able to apply their existing knowledge with improved techniques, resulting in safer buildings that they could construct themselves.

While most organisations became convinced of the benefit CRAterre’s TCLA approach, some resisted dialogue about these methods. In some areas NGOs continued to propose building larger houses with reinforced concrete and concrete blocks, rather than using local building techniques.

Environmental and social impact

The environmental impact of the rebuild was a key factor in CRAterre’s work. Materials used in the building process – mainly earth and stone – are low energy and only a small amount of cement was used where necessary. Timber was imported when not locally available or abundant enough for sustainable use. In mountainous areas 95 per cent of materials were extracted locally, reducing transport and greenhouse gas emissions.

Throughout the process, care was taken to preserve the traditional mutual support culture in Haiti known as ‘Kombit’ to encourage community resilience and avoid future dependency on external aid. CRAterre’s participatory approach also paid special attention to the inclusion of women. By embracing and building on local knowledge, the organisation was able to strengthen social ties and support local people to make informed choices.

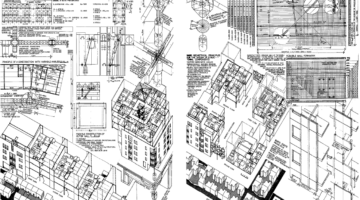

It is estimated that the total cost of the work CRAterre was involved in is around USD$19.8 million, however, because it linked to multiple projects with many partners that were funded from a variety of sources, a ‘traditional’ budget is hard to obtain. The results of its work, however, can be seen on the ground. Technical support provided by CRAterre enabled the construction of 1,150 new buildings and the repair of 500 following the 2010 earthquake. Twenty-five community and public buildings were delivered with support from the organisation and 850 local building professionals were trained in addition to staff in 15 international organisations. The reconstruction and repair projects were carried out in communities where people could not afford to rebuild themselves.

CRAterre also developed teaching materials, which were made available to vocational schools, and wider adoption of building techniques promoted by the organisation by self-builders and wealthy individuals has led to the repair or rebuild of around 6,000 homes since 2010. The team also helped develop and shape advocacy campaigns, carried out educational activities and supported professional networks across Haiti.

By providing technical assistance to a spectrum of different organisations involved in the rebuild, CRAterre was able to achieve some much-needed continuity in rebuilding methods with far-reaching results. Local building techniques have been widely accepted and adopted throughout Haiti, including by government departments. In 2012 the Ministry of Public Works Transport and Communications certified a system for building timber frame houses, which was promoted by CRAterre.

The effectiveness of CRAterre’s approach was put to the test when Hurricane Matthew hit Haiti in 2016. Homes rebuilt using TCLA methods suffered significantly less damage than others, leading to wider adoption of the techniques by UCLBP, the government body responsible for national housing policy. Following the hurricane, a further 800 households were supported by CRAterre to repair their homes.

The future

Since 2010 Haiti’s recovery has been compounded by further hurricanes, storms, drought, disease, and political, economic and social disruption. The country’s recovery and efforts to rebuild continue under intense scrutiny.

While no further funding is in place to extend CRAterre’s TCLA project in its current form, the concept has been adopted by UCLBP, the Global Shelter Cluster (a global platform coordinating post-disaster response) and other humanitarian organisations working in Haiti. Its influence is also being felt at policy level and it has submitted documents to the Ministry of Public Works Transport and Communications to establish national construction standards across a range of building types.

CRAterre is still working in Haiti, collaborating with government authorities, universities and vocational centres and providing technical support, training and expertise to projects led by its partner organisations. Recognition and adoption of TCLA is expected to increase across Haiti and CRAterre continues in its quest to promote the TCLA approach at a global level.

View the full project summary here – available in English only