As a result of the 1990s wars, Serbia has the highest number of refugees and internally displaced people in Europe. The original government policy was to house the most vulnerable displaced people in collective centres. These provided shelter but conditions were frequently appalling with inadequate sanitation, water supply and little privacy. The centres were also in the process of closure. SHSE has played a significant role in providing new permanent housing for people enabling the collective centres to be closed. It offers quality housing, individually tailored support services from local social care institutions and connects people to a local “host family” who provide additional support to help people re-integrate into society. The project has been extended to other vulnerable groups including homeless people, vulnerable people and Roma.

Project Description

What are its aims and objectives?

The SHSE programme has been in place since 2003. The aim of the project is to improve the housing conditions and social inclusion of the most vulnerable groups in Serbia. The programme was initiated to provide permanent decent housing so that the most vulnerable forced migrants could be rehoused from Government collective centres built as emergency shelters to house people who had been displaced during the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.

Government policy was to close the shelters but because of the lack of institutional mechanisms and insufficient capacity of social housing, they remained open long after planned closure dates. The centres provided extremely poor quality housing, with poor sanitation, overcrowding and insanitary water supply and, most important, produced further social exclusion of their residents. Whilst some still remain open today, the work of SHSE helped house many people and hastened the closure of many collective centres.

The project has built 1,014 homes so far, housing 2,643 of the most vulnerable and socially excluded people. It also provides individually tailored support to enable people to integrate back into society and lead independent lives. The individual needs of the tenants include finding work, acquiring health care and social care services, psychological support and relationship building within the local community. These are provided through the host families system and social work centres, which jointly provide a supportive environment.

Host families are families who face housing exclusion but have sufficient social capital and personal skills to enable them to act as good neighbours, helping new families find their feet and gradually become self-reliant. Host families live in an apartment in the same way as the other families requiring support.

Social work centres manage the buildings, educate, monitor and support the host families and also provide direct, professional services to beneficiaries.

Housing Center is an organisation which has, together with other partners, developed and implemented the project. It organises training workshops for beneficiaries of the project and organisations and institutions at local and national levels, carries out research on housing for vulnerable groups and works with the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy and Commissariat for Refugees to develop guidance on social housing in supportive environments in other regions.

Housing Center shares its learning externally and currently it is a member of FEANTSA (the European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless).

What context does it operate in?

Serbia has a population of more than 10 million and has the highest number of refugees and internally displaced people in Europe. The situation is a legacy of the wars of the 1990s. Twenty years after the wars ended, the country still hosts 45,000 people with refugee status and has 205,000 internally displaced people.

Refugees and internally displaced people are the poorest and among most deprived in Serbia. Their unemployment rate is 33 per cent, far higher than the general population. Incomes are low; 29 per cent have incomes below 48 Euros a month. Sixty-one per cent do not have a permanent home. Many of them are accommodated in the collective centres or inadequate private accommodation.

Serbia has one of the largest Roma communities in Europe, with a population estimated to be around 500,000. Roma people are among the most vulnerable communities in Europe, with a long history of persecution and discrimination. The Roma communities are amongst the most deprived and socially excluded groups in Serbia. Although Serbia adopted a law on Social Housing in 2009, it does not have a functioning social housing system. Very few of the requirements of the Social Housing Law have been implemented. The private housing market has not been able to serve the most vulnerable people, due to high rental prices and rising demand. Estimates indicate that there is a shortfall of 100,000 homes in Serbia; this increases both the demand and the market price for homes that are available. Housing is not seen as a political objective and it has neither a system of affordable or social housing nor a housing policy in place.

What are its key features?

The SHSE project provides sustainable housing solution to the most vulnerable people. It helps them develop the skills and competences required for a self-reliant and independent life.

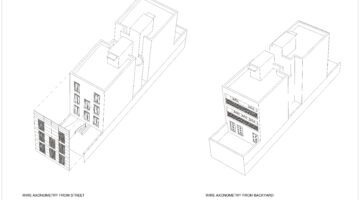

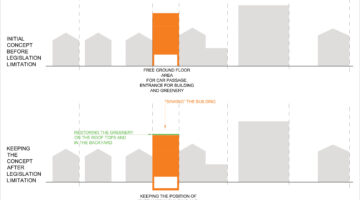

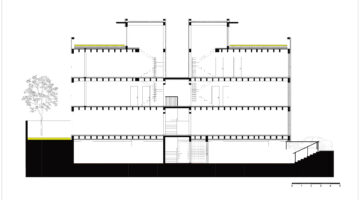

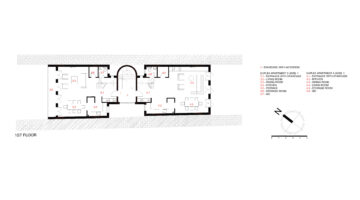

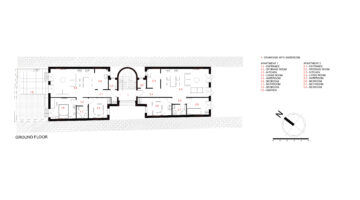

The role of the SHSE service is not only providing housing but helping residents become more included in society. The project has two main components: The construction and provision of social housing units and creating a supportive environment, which further facilitates social inclusion.The social housing built by the project is specifically designed to help encourage integration and communication between residents. The buildings have a mixture of different sized apartments allowing a diverse mix of households. Special attention is given to common areas – common living rooms, laundries and outdoor spaces. The project recognises that these are the areas where social contact and communication between residents take place. Setting up of the supportive environment component includes:

- Selection and training of the host families, who help families adjust to a normal life and provide assistance for networking and building relationships with others.

- Training of the social work centres, which continue to support and monitor the progress of the tenants after the project is over.

How is it funded?

The first SHSE projects were financed by Swiss Development and Cooperation. Since 2003, 20 million Euros have been invested in the capital costs of building. Ninety per cent of this has been provided by international donors, including UNHCR, the European Union and the German government. The other 10 per cent was raised locally through local government and local donors. Projects were also included in the National Investment Plan of the Government in 2009.

Land and infrastructure connections are provided by local government as their contribution to the project. Local government also takes responsibility for building maintenance and providing support services for residents through local social care centres, which it funds. In return, the ownership of the buildings is transferred to the local authority.

What impact has it had?

The project has successfully helped provide good quality housing and support in social inclusion to over 2,500 people. Evaluation work carried out shows that resident satisfaction levels are extremely high.

The project has enabled numerous collective centres to close. Over 2,000 of SHSE’s residents were rehoused from collective centres.

The project has influenced national policy. It was influential in the current national housing strategy, which recommends the SHSE approach be used for internally displaced people.The project was also used by the government as a model in developing a strategy for decentralising social welfare service.

Why is it innovative?

- The key innovation of the project is to combine housing provision with social welfare support through Centres of Social work. Helping groups to leave the collective centres and start an independent life integrated with other parts of society.

- Introduction of the Host Family to provide peer support. This support is available close to where people live and the hosts have the same ethnic background, language and family situation.

What is the environmental impact?

The SHSE buildings are thermally insulated and energy efficient. New regulations on energy efficiency in Serbia promote the thermal performance of housing. Compared to the collective centres and also to the housing generally in Serbia, the new buildings are far more efficient. Most of the new buildings have more efficient energy and water usage. There is a positive environmental impact, as the old collective centre buildings were badly insulated, used old schools, gymnasiums, agriculture warehouses and factory buildings. The buildings were neither designed nor insulated for human use. The closure of these centres has had a positive impact on the environment and the people living in them.

Is it financially sustainable?

The project relies significantly on international donors to provide the capital costs of buildings.

This model will be used in the immediate future.

There is a strong interest amongst donors to assist with finalising the refugee housing situation in Southern Europe through the Regional Housing Programme and so the prospects for future funding are good. In the future the project hopes that the financial stability of the country will settle to the extent that it will be possible to borrow capital from lenders, with additional funding provided through local government.

What is the social impact?

The project facilitates a system of mutual support and leads to greater community cooperation. The beneficiaries, host families and local community take responsibility for arranging a number of support measures together. Transferrable skills also identified from within the community are shared. In the many municipalities psycho-sociological support, learning assistance, computer training or employment assistance are provided in common living rooms provided within the buildings. The project enables people facing housing and social exclusion to acquire various forms of support (obtain citizenship, access health and social care services, increase their employability) facilitating their social integration. The approach adopted by the project contributes to improved health and safety, since special attention is given to architectural design, materials used in construction and construction standards.

Barriers

- Political instability, frequent shifts in power and conflict between political parties and struggle over land allocation has been a major challenge, which has affected the level of government support the project has received.

- After the collapse of the socialist political system and mass privatisation of social housing, the market was expected to provide housing to the most vulnerable. This has not happened and the policies and strategies have been delayed. This gap has led to the adoption of illegal self-help strategies.

- Many project beneficiaries have been living in government and donor-supported collective centres for many years, in some case 15 years.

- While Centres for Social Work and local self-government are enthusiastically working in the creation of an inclusive society, the other tiers of the political system and government are still struggling to wholeheartedly adopt the changes.

- Housing construction is expensive and financial allocation is a challenge. The administrative processes for the allocation of land and construction of building are time consuming.

Lessons Learned

- Housing with integrated social support is important. Housing alone is not enough and continual, long term and individually tailored support is crucial because of the multiple vulnerability people face. SHSE learned that integrated and targeted support is the most important part of social housing.

- The importance of constructing the buildings in central locations and integrating families from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

- National legislation on Social Welfare provides a general framework, while a number of decisions are taken at the municipal levels. At this level diverse needs of the families are recognised.

- More investments are required at the beginning, especially as the host families require support and beneficiaries develop their knowledge and skills. Once, beneficiaries gain more independence, the support required is only occasional.

Evaluation

In 2005, evaluation was carried out by SDC. In 2010, UNHCR carried out some evaluation. In 2009, the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy conducted some evaluation. All the evaluations endorsed the impact of the SHSE programme.

Transfer

The project has scaled up and is operating in 42 municipalities. The local governments would like to use the approach to address the needs of low income populations, not just refugees. The project learning has been used in Armenia and Georgia with support from SDC.

At a national level, the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy has supported the exchange visits and training of staff in other municipalities. It has supported the networks of Centres for Social Work, the final beneficiaries and the host families so that they learn from each other.

With the support from Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), the positive experience has been shared with organisations in South Caucasus, Armenia and Georgia. Study visits have also taken place to Georgia and Armenia.